At dinner on the third day, Nate looks up from his plate and asks the question.

“Why did you die?”

It is the first time he has opened a conversation since Em arrived. For the last three days, he has communicated mostly in monosyllables and glances, only speaking in sentences if he has to give her instructions.

Em ponders the question but remains silent. Perhaps a human would try to answer, but her hardcoded programming warns her not to. Too often such whys are answered too quickly, blithely, or philosophically. Instead, she lets the question hang, lets the silence grow longer and louder until Nate looks away and resumes pushing his food about his plate.

She reaches out and puts her hand on his left hand, which is resting on the table. Squeezes it.

His grief is normal.

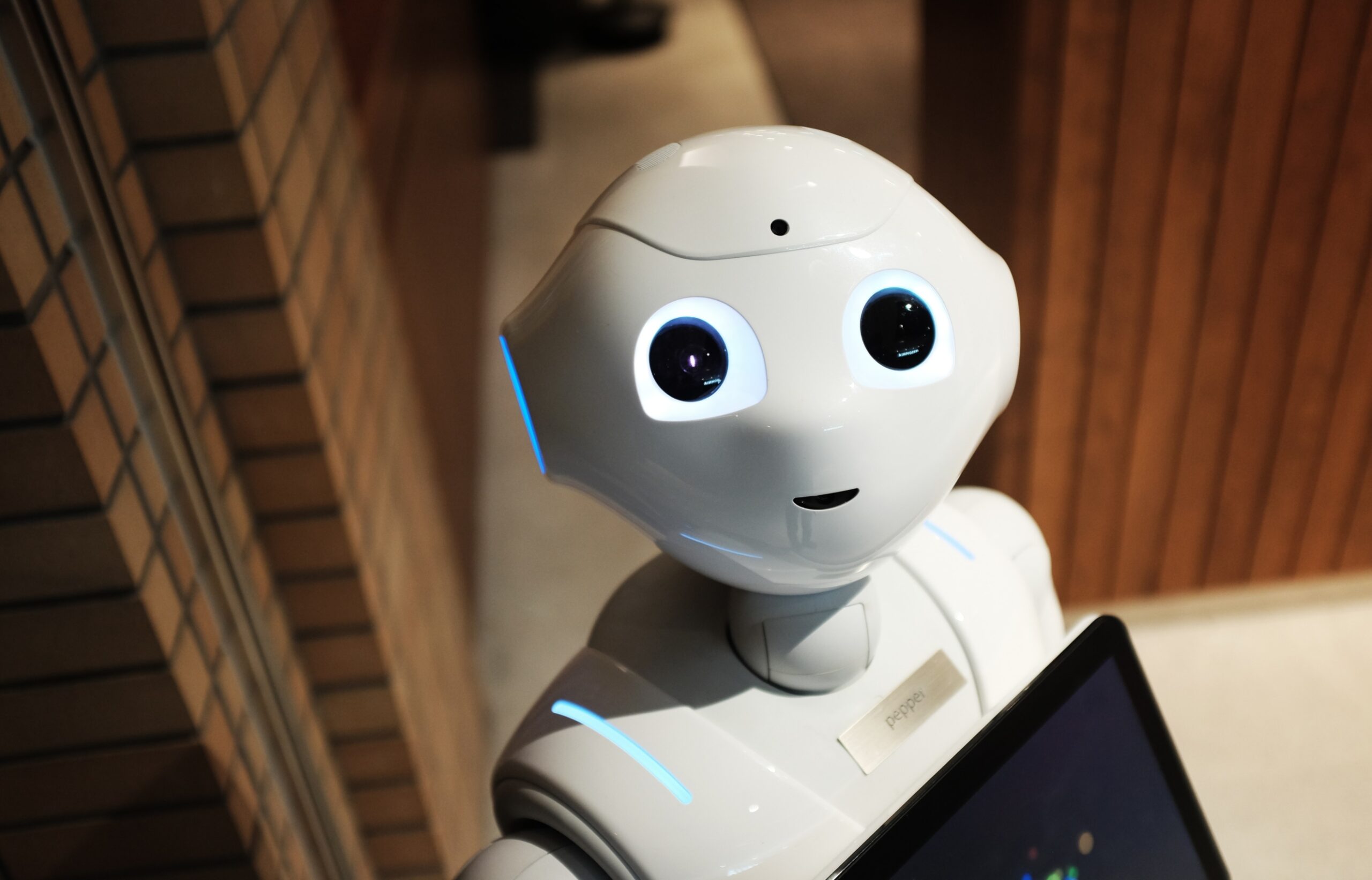

Em’s AI model has been trained to recognise different kinds of grief, and his reactions do not depart from the mean. Though she does not remember the clients in her past lives—the data is anonymised and added to her data set after each contract—seven of her past dozen clients had asked similar questions of her when she was consoling them, most recently when she was an elderly gentleman tasked with tending to his grieving widow.

As she watches Nate, she visualises what could become of him when her time ends, and her inventors clear her memory of him, reconstruct her appearance, and send her to console another bereaved client.

She stands and comes around the table. Sitting down next to him, she puts an arm around his side, and when she does, he leans onto her shoulder. She puts her other hand on his knee.

They sit like this for a long while.

Finally, Nate straightens, and as he does, Em recites one of the human Emily’s most oft-repeated texts to him.

“I love you so much.”

Nate cannot meet her eyes. Finally, he mumbles, “I loved you too.”

###

This is what Emily would have done if she broke up with Nate: blacklist his number, block him on social media, delete their photos, and move out of their house—well, his house—all in one day. She’d done it to her previous boyfriends and had no qualms repeating it.

Except she did not plan to repeat it with Nate.

And so she sits, hands clasped so tightly they’re white, as she hears Nate say the words she has heard before, has said before, and never expected to hear in this house, from his lips.

When he finishes, she speaks.

“There’s someone else.”

He shakes his head.

“Then why?”

He looks away, then says, “It’s hard to explain.”

“Try.”

Nate swallows. “I’m trying.”

But as he searches for the words, Emily realises she doesn’t want to hear them. Not another, it’s not you, it’s me; not another, I don’t feel the same way anymore; not another, you knew this was for the short term.

Emily stands, eyes blurring with tears. She turns and runs into their room, forgetting it’s not hers anymore, it’s just his.

She shuts the door. Falls on the bed.

Why?

In the past, Emily could recognise when her relationships had reached their third act, with both sides just pantomiming love until the final curtain.

But not this time.

Why else would she decorate their—his—home? Post pictures with him online? Move in with him?

Or sign that android bereavement plan together, which would send one of them an android in the likeness of the other if either were to pass away?

Outside, she hears movement. Nate crosses the living room towards the door. But doesn’t knock, doesn’t enter.

After a while, he steps away, but by this point, Emily can’t hear him past the roar in her ears.

###

They sit on the couch, Nate eating and Em watching, arm’s length apart. While Emily would’ve wanted to be nearer to him, to hold his hand, to lean on him, Em has to keep her distance. To grow her distance. Every week she has been programmed to increase the amount of physical distance between her and Nate, and to decrease the amount of time she spends with him. Em, after all, is not a replacement for Emily, but a vehicle to ease the transition between Emily’s presence and absence.

That doesn’t mean, of course, she can’t comfort him in other ways.

And so, while she keeps her distance and picks at the couch fabric—another habit of Emily’s—she watches Nate eat the goulash she prepared for him.

At the moment, he’s silent, but she doesn’t need verbal affirmation to recognise her success. The way his eyes close at each spoonful, the way he sops up stray gravy with the bread she baked, and the way he’s completely ignored her from the moment she set the dish in front of him is enough.

She’d suspected he was craving this. Not that he’d mentioned it. But she’d reviewed their grocery receipts, text messages and shared photos and had concluded it was one of his favourite dishes.

And besides, all the ingredients had been in the kitchen.

It felt almost as if he were hoping—despite the fact she was a robot—that she’d know how to make it.

But despite his good mood and double helping, Nate falls back quiet once he’s washed the dishes, and so Em is prepared but disappointed when he finally asks the question that has been creasing his brow the past few days.

“When you died, did it hurt?”

She leans back, unsure how to respond. Previously she’d brushed off the question, expecting him to lose interest in those details once the shock wore off, but increasingly she’s concluded that unless he gets closure on this subject, he will not improve.

In truth, she cannot answer for certain. Emily didn’t wear dolorimeters to track physical pain, which means anything Em says about the situation would be speculative.

She can, however, make an educated guess. As a robotic replica of Emily, her memory caches—all ten terabytes—contain all of Emily’s retrievable data, from text messages and emails to browser history to biometrics from her wearables and vehicles.

The last thing Emily’s vehicle recorded was a collision at highway speeds, with all air bags deploying.

And so Em says, “It did. It hurt immensely.”

Nate’s face doesn’t change.

He asks, “How did you feel?”

Em bites her lip, and her processor parses the question again. The question is in the past tense, but Em doesn’t know what Emily felt at that point. Guessing levels of pain is one thing. Guessing Emily’s private thoughts, unwritten and unspoken, is another.

She is about to give a generic I can’t remember when she catches herself.

That answer will not help. What could she say that would help him more?

But Em knows she is grasping at straws here. Unlike humans, she can’t lie. It’s not just a matter of robotic ethics. Lying requires a level of invention, creativity, and risk-taking her designers were careful to exclude from her behaviour, which means even if she wanted to lie to help someone, she doesn’t know where to begin, what to fabricate.

What she can ascertain from the data she has is that Emily’s pulse shot up before the blood loss set in.

And so she says, “I felt terrified.”

After a moment, Nate nods, but Em can recognise his expression from photos and general AI datasets she was fed.

He’s not satisfied with her answer.

###

The cupboards have disgorged all of Emily’s things, and they lie in unsorted piles on the couch, the coffee table, the dining table, and the bed.

On the floor, Emily has laid four bags: two she brought when she’d moved in, one she bought for their trip to Croatia, and the other for their camping trip to Montana.

When Nate had seen the amount of things spread across the house compared to the size of the bags, he’d offered to give her one of his.

She declined. He had already allowed—expected—her to stay until she found another place, but she was not going to accept any more kindness from him. Any more and she would begin to feel like a daughter or a roommate.

No, Emily plans to leave with her head held high, her status as girlfriend—ex-girlfriend—intact.

Except she has no plan of when to leave.

The moment he told her he would let her stay until she could properly move out had been a spark of hope—perhaps she could win him back, show him her love, do something to make him change his mind.

She’d even hatched several plans. She’d bought ingredients to make his favourite dishes—ravioli, quesadillas, goulash. She’d dressed nicely, even at home. She’d even helped him iron his shirts.

Still, he asked her to sleep on the couch.

But Emily still holds out hope he’ll change his mind, which is why, despite all her busyness in packing, she has not set a date to leave, not called any friends in town asking to crash, not called any landlords enquiring about rentals.

But she is not foolish either. He has moved his toothbrush away from hers, has taken to putting her piles of clothing straight into her bag when he needs space on the dining table, and his replies to her in person and on text have steadily shortened.

She imagines the next step would be charging rent, and she plans to be gone before that happens.

###

“You think I killed myself.”

Em has thought about her interactions with Nate over the last few days, running the instances through her processor and integrating it with her AI behavioural model, and after a week of enduring his specific line of questioning surrounding the events of Emily’s death, she is sure that is what he wants to know but is afraid to ask.

Nate twitches at the question, and he sinks into the couch before he replies. “Did you?”

Now it is Em’s turn to twitch—though, as a robot, she manages to override this urge before it executes. She had been prepared for his denial—had mapped out a response tree for that—but wasn’t sure what to say if he affirmed it.

Not that she doesn’t have her suspicions on whether Emily had killed herself. From the speed of her driving, to her heart rate, to the charge left in her electric vehicle, the data seemed to point in one direction.

The problem is not what Em thinks. The problem is what she wants to tell Nate.

And she’s not sure telling him what she suspects will help his recovery.

So finally, she says, “I don’t know.”

Nate cocks an eye at her. He beckons her to sit, and so she does, on the opposite edge of the couch. He crosses his legs, and she copies.

He says, “You say that, but I want you to tell me what you know.”

Em reflects on the request. She shakes her head.

“I can’t do that.”

“Why not?”

“I’m not a book, Nate.”

“But you’re a robot.”

Em looks into his eyes. It’s the first time he’s stated that fact, and according to the milestones her company has set, this is a big step.

But she knows the way he has said it does not indicate recovery. She continues.

“I am, but I have rules to follow too.”

His eyes narrow, but then he looks away. “Is there anything you can tell me? Anything at all?”

Em leans back. She is prevented—by law, company policy, and Emily’s own historical behaviour programmed into her—from telling Nate certain things. She can’t recite browser history or personal messages, medical details or passcodes.

And while that leaves a lot she can still tell him, none of it conclusively provides the answer Nate is seeking.

And she does not want to make him believe a lie unintentionally.

Nate seems to understand when she explains this. He stands up, and stiffly pats her shoulder. “It’s fine,” he says, but heads into his room and shuts the door with a clack.

###

She told him she would move out this week.

That hadn’t been Emily’s plan.

But when he had asked her on Sunday whether she’d begun looking for places, she had reflexively given a date of departure.

She was not going to back out now and beg for more time.

She would book a hotel or something.

As she sits on the couch sorting out her remaining items, she inspects her four bags, so carefully packed and repacked.

Three years of possessions.

On the couch next to her is a letter she has spent the better half of the week drafting on her phone. It had taken her ages to find the words, eons to express the feelings and thoughts she wanted to leave Nate. What he meant to her, what she’d hoped of him, what she’d hoped they’d be.

Her final goodbyes.

She has already blocked him on social media and will delete his number later.

There is no point in having either.

But suddenly Nate is home, and Emily has shoved her letter under a pile of stationery she is sorting.

He looks at the bags in the hallway.

“That everything?” he asks.

She half nods. “Not everything,” she admits. Then, blocking his view of the pile with the envelope, she adds, “I’ll clean up the rest today.”

He nods.

Emily shakes her head and remains silent until he leaves, then slips the envelope into a folder. She will hide it later for him to find; she does not want him to read it too soon.

###

He is sitting on the couch with his laptop; she is sitting in the dining area, head resting on the kitchen table when she makes her announcement.

“I’m leaving on Sunday.”

Nate looks up at Em. He says, “I see.” He snaps his computer shut, walks over, and sits in the seat next to her.

She feigns indifference. Em had hoped Nate would not come over, that he would ignore her statement and go back to work, but it seems he is not going to.

She has been monitoring him all week with these little games, trying to see if he’s adjusted to life without Emily and whether he will survive the Emily-shaped void in his life.

The results are mixed.

According to her recovery rubric, a perfect recovery is one where the bereaved does not desperately cling to her presence but also does not make serious efforts to avoid her presence; she should be treated like the background.

But Nate still seems too aware she is there, swinging between avoiding her presence at all costs to spending excessive time sitting next to her, as if sitting in silence would absolve him of some great sin.

She knows what he wants, of course. And so every night when he goes to bed, she lies on the couch and searches her memory, analysing every event that seems tangential to Emily’s death—text, photo, heartbeat, browser search. But she cannot find it. She cannot find any significant scrap of information that would allow her to tell Nate, No, she did not kill herself. And I have the evidence to prove it.

She can’t search online for more information either—as modern and equipped as her body may be, her creators did not feel it safe—for her safety and theirs—to give her wireless access.

Out of the corner of her eye, Em notices Nate watching her. She avoids his gaze. Closing her eyes, she begins to review the facts of the actual accident once more.

###

The windshield has shattered, the guardrail has crumpled the hood, and Emily is coughing blood onto the dashboard. The car’s computer has buzzed emergency services, but as she struggles to sit up, that is not on her mind.

She coughs again and winces as a gust blows through what remains of the windows, which are beginning to frost over.

Her vision flashes white.

Her eyes dart back and forth across the snowy landscape, and she feels the cold creep up her ungloved fingers, her uncovered face.

Emily’s vision flashes white again.

Her eyes land on the cracked digital screen next to her steering wheel, and for the first time, she remembers that her vehicle can contact an ambulance, has contacted an ambulance.

She wonders what Nate would think. They had barely exchanged goodbyes this morning—he not knowing what to say, she having said all her goodbyes in her letter—and their final hug this morning had been hypothermic.

The letter.

She cannot remember what she said in it anymore. She strains to recall, but it is too late—her blood is on the dashboard, her coat trickling onto the seat.

All she remembers is that it was important.

And so she gurgles that word hoping a device would pick it up, over and over, until it, too, has lost its meaning, and then she, too, goes quiet.

###

At two a.m. on her final night in Nate’s house, while looking for some shoes to wear, Em finds Emily’s final letter to Nate tucked in one of her old shoeboxes.

She’d been delivered to the house by a company tech and hadn’t needed shoes since she arrived—since androids like her are not allowed to leave the bereaved’s house—but wanted to wear a pair when she left.

She had planned to wear the sneakers she knew Emily had left behind.

As she reads the letter up and down, she searches her database for anything similar.

And she finds it: a document containing former drafts of this very letter.

As she compares the contents, she realises it will not do. Emily’s final message will not help.

But an earlier draft will.

Tiptoeing into the study, Em pulls out the box of stationery Emily had used to write her letter. Pulling out the same pen and a new card, she painstakingly writes out the earlier message.

Dearest Nate,

If you’re reading this, I must have moved out already.

I don’t know what to say that you haven’t already heard. I love you. From the day you drove me home in that snowstorm. And I still do, and will for a long time more. And so I do not know how to say goodbye because I don’t want to. I wanted us to be forever, for death to part us rather than life.

But you have made your choice. I don’t like it, but in leaving, I, too, have made mine. We will live apart, we will grow apart. And so, while I wish that our happiness could be together, I wish you all the happiness that I had being with you and that your future relationships will not sour for you like ours did.

I won’t waste your time any further. Know only that I love you so.

Emily.

Then seals it in a new envelope and deposits it into the shoebox.

Em tucks the original letter into her blouse, and then steps out of the house barefooted and sits on the porch step, where fresh snow is gathering.

She will be gone before he wakes. Her company has found it works best for the bereaved that the androids are picked up quietly in the morning.

Em wonders when he will find the message. What will he do when he reads it? She hopes he believes the letter and takes it as Emily’s final words.

She wonders what her company will do when they review her actions. Will they accept it as good practice, or will they hardcode new rules in her future iterations, preventing them from doing what she did?

It doesn’t matter to her. In twelve hours, they will anonymise her memories with Nate, add all their interaction data into her data set, and begin giving her a new face, new body, and new memories for her new job.

Around the corner, she sees the yellow light of her company van beaming down the street.

Em stands. Dusting off the snow, she turns and with artificial lips, whispers words that cannot be heard towards Nate’s house.

Then she turns towards her next life.