Chapter 1

Lane explained that we weren’t allowed real names only after she hired me. “You’ll be ‘Foxtrot,’ she declared. She convinced me that my new name fit perfectly. I couldn’t be ‘Bravo’ or ‘Charlie,’ because both of them were still alive, but she couldn’t legally say where or when. ‘Zulu’ seemed insensitive, ‘November’ was confusing, and ‘Juliet’ or ‘Romeo’ were off-limits because, “That’s just bad luck. We all know how they ended.”

And back then, I wanted myself to be as graceful and composed as the first steps of a foxtrot, not needling and frenetic. Lane flashed a smile, green gum in the corner of her mouth. Apparently, she always roped in new contractors that way, grinned, and told each one privately that they were her favorite employee. But the reality was obvious to anyone with a single, sputtering neuron: anyone willing to do the job was her favorite employee. Few, if any, were willing to travel through time, and with a single misstep, you’d be out the door and flat on your ass.

Lane really loved our clients, more than the slew of contractors working under her and far more than her daughters in boarding school. She was — and may still be — the only person ordained by the company to pitch our services to clients, all firm handshakes, polo clubs, and knocking back mimosas at noon on a Tuesday. Our clients were a special breed of affluent, born from a dozen generations of compounding wealth from patents, property, and pillaging continents. What Lane sold these ultra-rich were one-way trips through time. They purchased the privilege of relocation to an era before the societal collapse that Warren assured them would arrive imminently.

“End of the world, basically,” Lane said flatly after I signed the nondisclosure agreements on my first day. “Like everyone and everything disappears. It could be the environment. Warren believes that theory, at least. Maybe someone drops a nuke.”

As the company founder and chief of operations, Dr. Warren explained it better during the afternoon onboarding session. “It’s unknowable by its nature. It has no clear origin, but the event is certainly devastating. Humanity is assumed to go extinct. We can’t observe the moment directly. We don’t know how the collapse occurs, only when it happens.”

“And nobody knows? Except you?”

“Clients are by invitation only, so very few outside this facility,” he conceded, eyebrows hidden by tortoiseshell glasses. “But the public has no idea. It would be difficult for them to firmly grasp the reality of a global collapse.”

To convince the suspicious clients that he wasn’t some charlatan, Warren took each client’s hand and whisked them deep into the past, often to a landmark in their childhood. If the client required further evidence, they re-entered the testing chamber donning hazmat suits to witness the aftermath of end times. Most clients left with giddy smiles and returned frazzled, rigid, eyes wide. But Warren prodded them with irreverent comments until each client would bend and relax again. I traveled there with him once, squinted up at the blood-red sky, the lifeless landscape peppered with dead brush and skyscrapers that had collapsed like sandcastles and fallen into the ocean.

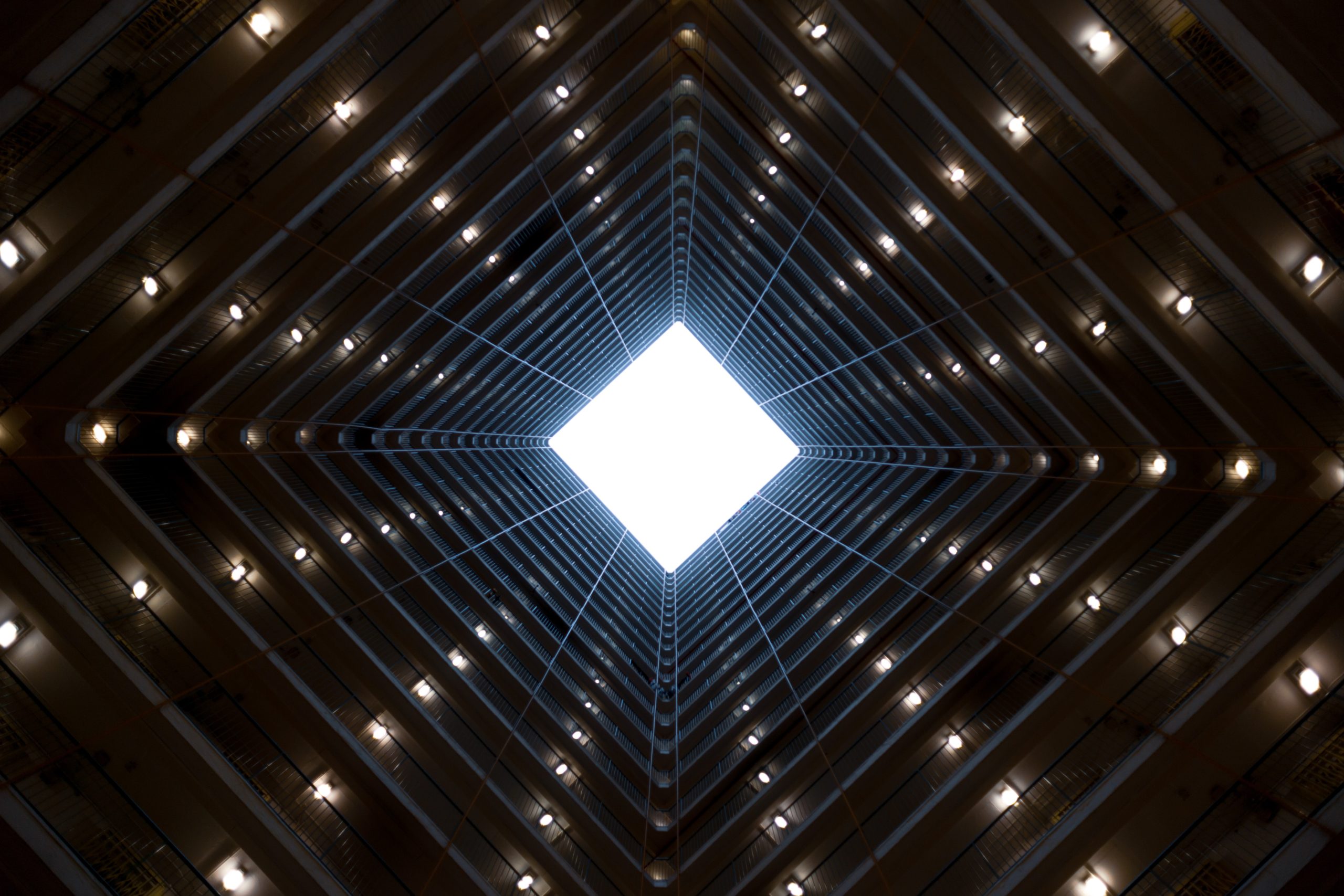

Later that night, Warren told me about his discovery of the end of the world. I prompted him with a polite question about the machine, and he immediately sauntered to the testing chamber. I followed through the five-spoke vault doors, drawn by his sudden delight. I imagined the machine was sleek like Warren’s office, instead crammed into a glass box, teeming with tubes of blue coolant, inductive sensors, and unfinished edges that cut like teeth on knuckles. Blindfolding yourself before traveling was strongly encouraged to block the seizure-inducing flashes, a Biblical flood of violets and reds. But I grew to love the machine’s roughness, its function over its lack of beauty. I became used to the vertigo during arrivals and departures, to the sulfurous scent of burnt hair that permeated the testing chamber and clung to clothes.

Warren spoke with his hands, ringless and scarred, tracing shapes into the air so that I could pretend to understand. He had abandoned a professorship to avoid the constrictive red tape of academia and prototype his machine. After he landed in 1723 by mistake, he realized the potential of his invention and its consequences. He sprang violently to his feet to demonstrate lifting a failing company from its knees. I stifled a laugh when he slammed down on his tailbone, yet never missed a beat. Drowsy, I watched him, comforted by the claustrophobia of the testing chamber and the lull of his tirade. I would come to love his tirades.

Very few employees at first, Warren emphasized. All of the company’s work was very hush-hush early on. Rumors of his machine spread among wealthy circles while he drafted early travel protocols that wouldn’t kill passengers. They all begged for a spin despite the early test animals — mostly basset hounds and macaques — that rarely returned intact. Warren smirked darkly when he told me that, and yet he also tipped his hand, his unease briefly palpable, disturbed by how clients burned their cash to avoid the apocalypse. How quickly they left behind the weight of their lives to leap off what could have easily been a cliff.

But he returned to event horizons and uncertainty principles and what happens if you kill your grandpa by mistake. How overnight he secretly became the richest person on Earth since the ritzy trips to the beloved periods of American history proved so popular. Lane espoused an idyllic view of those eras to investors at venture capital meetings. She skipped over the fistful of clients married to dreams of the Wild West who died painfully of cholera.

“There are ground rules, too,” Warren added with a lopsided grin. A kissable grin, I thought then, but I think now I would’ve assumed a stroke was imminent. While most actions are like spitting in the ocean to raise the tide, even minor disturbances can have outsized effects. “Our contractors are our biggest assets. We sometimes need brave souls like you to intervene.”

Warren was slightly wrong and slightly right. “Intervene” is too sanitized. Get too lucky buying stocks? I pay you a visit with a warning. Don’t listen and crash the markets shorting oil futures? I clean up any leftover paradoxes and drag you kicking and screaming back to the present, or much worse. Show up in a history textbook or fuck your great-great-aunt Suzie, and the same policy applies.

I draped my arm around Warren, eventually. I set my head against the concrete wall, then on his shoulder by late evening. I told him about my mother, about her shouting after my schoolyard fistfights in Queens. Our bitter arguments when I was fifteen that convinced me to disappear in the middle of the night. My fury at the malignant cells that later blossomed in her blood and seeped into her brain. But Warren held me, comforted me without pity. He distracted me with stories of Lane’s melodrama until I laughed, and the heat dimmed in my chest. He lectured on the differences between fission and fusion, punctuated by my fingers lightly brushing against his. This blurred into a conversation about how little we each believed in God. That point would be rehashed a week later during our first of many private dinners billed as work meetings.

When I later asked when he, like his clients, would leave the dying world behind, Warren shifted as if his skin had become a tight, cheap suit. That look appeared after we would fight about him forgetting to return calls, interrupting my suggestions during shareholder meetings, his perpetual lateness, anything he believed not worth discussing. Warren answered most probing questions with cagey half-answers and tautologies. His dry humor undercut attempts to dissect those topics. He often guided those conversations in new directions, such as towards his obsession with sketching pre-industrial sunsets or saving pottery predestined for destruction by careless museum owners. This behavior repeated when I asked about his family. What kept him up at night? Why we had to leave his apartment at different times so we wouldn’t arrive at work together? Why us taking a break really wasn’t the end, but just that: a break.

But I let it lie. He knew I wouldn’t press, and I wouldn’t for nearly a year; my tolerance was always justified by his devotion to saving humanity. His mind was fragmented by pressures beyond what I could fathom, I reasoned. He suffered privately. His outburst and blunders and missed deadlines for investors were outliers, not rules. That first night, I only gazed at him admiring his life’s work. Sparks danced across the machine’s antennas that I learned later manipulate the Earth’s magnetic fields. He never fully explained their function to anyone, or how the capacitor works, or why he would eventually disappear and pitch himself into the yawning void of history. Not even to me.

#

Even after we split and Warren vanished, I’d slink by his office, pray to find him grilling his scientists on cesium production forecasts, arms folded and feet up as usual. I convinced myself it was really a blessing to avoid the passing hallway glances, the snide comments, and excessive critiques of my reports. That I actually enjoyed spending my twenty-fifth birthday alone, bare feet dangling over the Hudson with a stolen bottle of pinot noir.

“He’ll turn up soon enough,” Lane said, with an exaggerated hand on her hip, a performance designed to obfuscate how much she savored Warren’s absence, the responsibilities and job titles she accumulated because of it. “It’s unlike him to travel without logging his trip.”

At times, I would relish in rescue fantasies. Effortlessly hauling a bloodied Warren to safety. Fending off sabertooths with a burning torch. Killing, if I had to. But then a week passed, and another. I kicked over the Rodin sculpture in Warren’s office. I tossed my keys to his apartment off a bridge in 1671. An unpaid intern handed them back fossilized in limestone. I still thought of his quips, his infrequent reminders to leave no traces in the past, take only pictures and clients. They lodged in my mind like fiberglass in fingertips. A full month after Warren blipped out of existence, I buried myself in work instead, stopping in my own era only to sip lukewarm coffee and sleep slumped in rolling office chairs.

I gave a stern warning to a couple who attempted to beat Edison to the patent office. With a silver tongue and silenced pistol, I convinced an irate semi-famous author that living in an adobe house without plumbing or tetanus shots wasn’t all that bad. I quelled a minor rebellion from the Harrisons, a dynasty of nuclear energy tycoons in their former lives. Having found colonial America unexciting, they established an evangelical denomination that denounced false gods and idolized their family members as apostles. I snapped when their followers (nearly) burned me at the stake. The father landed face down during his sermon, the two sons while staring at the hole in his skull, and the mother while boarding a charter to escape across the Atlantic.

But Paul Rigello proved more challenging. I think about him sometimes, not because his death altered any major timelines. He started the cascade of cause and effect, funneling toward what eventually happened to Warren. I visited Rigello on a Saturday, when the company parking lot had thinned enough that I wouldn’t have to indulge in any small talk. I skimmed his file twice in the testing chamber and threaded the aluminum buckles without glancing at the safety checklist.

After a few frictionless months of residing in the past, Rigello had become unruly and threatened, on several occasions, to kill the Russian diplomat and make the Cold War very, very hot. He seemed propelled by boredom, maybe by a wish to mold the future in his image. More likely, he thought playing spy might assuage his apparent mid-life crisis. I’m not sure. I don’t believe Rigello cared or even knew much about politics. It was my third time visiting him in two weeks, so perhaps he summoned a contractor with his antics purely out of loneliness. The ionizing radiation from my back-to-back trips would’ve made the regulatory department spit tea back into their cup, plus I hated visiting the 1980s. The period always felt garish, but I remember that day because even on Fifth Avenue, the air smelled unusually clean, the skyline not yet stained pale orange by distant never-ending fires and nitrogen oxides.

I weaved through traffic to the mid-century Hilton across the way. I avoided thinking about the specifics of entering a five-star hotel crawling with well-trained security and snipers on every rooftop. How much I’d have to pester Lane about her broken promises to pay my bonus for last-minute trips. How I’d do anything not to get shot and bleed out on the mauve carpet.

But I flashed a fake Bureau badge made of golden plastic and slipped inside the hotel easily. The Russian diplomat railed against inaction on sanctions. A crystal chandelier glittered overhead, the ballroom flanked by rows of stony men with wires in their ears. It was uptown chic with white tablecloths and palm-sized portions like the restaurant Warren had bought out for our three-month anniversary. I had hoped it was to impress me, and understand now it was to guarantee not running into anyone he knew. But Rigello recognized me instantly. He blotted sweat from the sharp cleft of his chin and lazily kicked out a chair for me to sit.

I reminded Rigello that I’d shoot him in the spine if he ran. His tongue flicked between dry lips, fingers dancing on his glass. I offered details about his wife, who had complained to Warren once about the alkalinity of the rainwater damaging her hair follicles. I lied that Mrs. Rigello had visited our offices and would arrive shortly, with their daughter, of course.

“Wrong,” he muttered. His legs shuffled under the table. “She’s been sleeping with the assistant I got her from a temp agency.”

I processed this development, eyeing the suited men strolling between the tables. I retracted my gun jammed against his kneecap, feathering the trigger, seething at how pathetically he clung to his wife. His indignance made fresh thoughts of Warren bubble up to the surface. I spat new threats in a church whisper, leaning ever closer, bullshitting harder. His obligation was to raise his daughter and fix what was broken with his wife by walking away quietly, I told him. Otherwise, his day would end there.

My threats felt as empty as my stomach. Rigello swirled his glass. His jaw flexed as if rolling uncomfortable thoughts in his mouth, but then he swallowed, and his expression grew infuriatingly placid. He declined with another mouthful of amber booze and joked loudly about tackling the diplomat. I shoved the barrel hard into the yellow fat of his thigh and repeated myself.

“I need you to really hear me, Paul. You’re violating your relocation contract. We’re not going to play Monopoly with global politics.”

Nothing.

“How about I paint your fucking brains on the wall?”

“Be my guest.”

I recognized my mistake when I forged the incident report. It took several milliseconds to realize red was blooming across the khaki fabric of his pants. I had somehow already pulled the trigger, so it was over and done before I could coo or threaten or do anything else. His knees hit the carpet, and the glitterati screamed, sprinted, ducked past tables, and the onslaught of security that swarmed the emergency exits like locusts.

#

After sex became habitual and Warren was exhausted by my complaints about black-tie dining, I suggested we take a trip. We learned sculpting for an evening from a tight-lipped Italian in New Amsterdam. My slab of white marble split after a few swift chisels, much to our instructor’s annoyance, so Warren let me sit beside him and work on his piece. I reveled in the privilege of watching him in his element. He patiently repositioned my hands and guided every tap, his blue eyes bouncing between the instructor’s work and his own. Yet it struck me how carefully he delivered each blow, that he quickly caught the tools I knocked over, and how he cut his stone into a small pyramid minutes before the Italian’s demonstration.

“Did you come here before?” I asked, withdrawing my hands to my lap. “Like, did you know that would happen?”

When he feigned ignorance, I called him “invasive.” The instructor politely asked us to leave during the proceeding shouting match. Warren crumbled and admitted to visiting briefly, but asserted it was so our evening ran smoothly. I eventually crumbled, too, apologized, and hugged him. I repeated the same routine after he announced our break, and I pleaded delicately for him to please, if you would so kindly, take me back.

I hypothesized what Warren might’ve advised for my situation with Rigello. Pressure on the wound. Elevate the leg. Alcohol, or hydrogen peroxide, if you have it. Certainly don’t haul him into the quartz bathrooms and out the fire escape. Rigello spoke little between violent coughs, palm pressed at the crook of his leg. My head swam with endorphins. I recalled Warren rambling about clotting factors and blood loss rates, but not whether the conversation was just before we split or much earlier. Whether it was between Mulberry silk sheets, or sitting in the red chairs of his office, or over breakfast in Park Slope.

I had plugged the bullet hole automatically, pressed an index finger on the wound like a sustained, breathy note on the clarinet. Anxiety tingled underneath my skin. Lane might fire me for needlessly killing another client, I thought. Banish me forever to some humanless era of history. There, for the first time, I pictured a future without Warren, the two of us permanently and temporally separated. I’d catch typhus, die alone, slip away anonymously, still thinking of him and his fucking machine.

“She hates me now,” Rigello interrupted, and I listened. “Knew it since we had the kid. Doesn’t matter now, though. She never wanted one, but I insisted.” Bloodshot eyes closed, tension leaving his body. “She stayed for the kid. Hoped to God that might’ve made her like me a bit more, but I don’t know. Maybe she didn’t like me before that, or stopped caring when I stopped. Or both.”

I envied his nonchalance. Envy like when I wished Warren would touch the nape of my neck the way he held freshly minted circuits.

I burned Rigello’s body in accordance with the protocol manual. Before he passed, he asked me, “Did she actually want to visit me? Or were you just saying that?” But I didn’t know. The question felt unknowable like his wife’s love, or Warren’s whims, or the state of Earth after humans made their exit.

#

My nose bled from the g-force when I returned seconds after I had departed. This happened more and more often in Warren’s absence, his machine sometimes requiring multiple attempts to make a successful trip. Despite repeated orders from Lane, the engineers only committed to minor repairs, likely terrified of receiving the blame if the machine broke down any further. I wiped my dripping nose with my white sleeves already marked with blood. All my clothing would be burned regardless to prevent contamination, and Lane wasn’t nearby to report the infraction. Mono-font type, email heading: how a certain unnamed employee bled everywhere, damaged clients and company property.

But, more than anything, I felt relief because Warren was gone, and this was good because I didn’t need him anymore. I blitzed outside to the balcony over Lexington Avenue, craving daylight and cigarettes. I struck a crushed Marlboro and let chemicals coat my lungs, although it tasted like sucking an exhaust pipe. I imagined, with contempt, a nauseating monologue Warren would never be able to deliver about our rise and fall. How we were more than just lovers, but partners cosmically meant to be, with assurances that Rome wasn’t built in a day, and a promise that, while difficult, our relationship would be built back better.

And then Lane interrupted my reverie. Shrieking, she wrapped her knuckles on the railing, pointed inside, blabbered incoherently. Her eyes flitted between my lit cigarette and sleeves stained pink, her rosy cheeks blanching. Before I could lie, she ripped me down towards the testing chamber, my hands suddenly wet with adrenaline. No time to harangue. No time to report my string of transgressions.

Panic surged in my chest at the figure crawling from the testing chamber, blindfolded with a black tie, dressed in a milk-white cardigan, feeling the empty air for a hold. His hands, bloodied and cut, looked recently wrapped and unwound with barbed wire. A younger, twenty-something Warren pulled off the tie and squinted up. His blue eyes met mine without a trace of recognition, then he bowed his head, as if in prayer at an altar. He sank to his elbows, muttered a panting, “Foxtrot,” and collapsed into a pile.