By Caitlin Taylor So

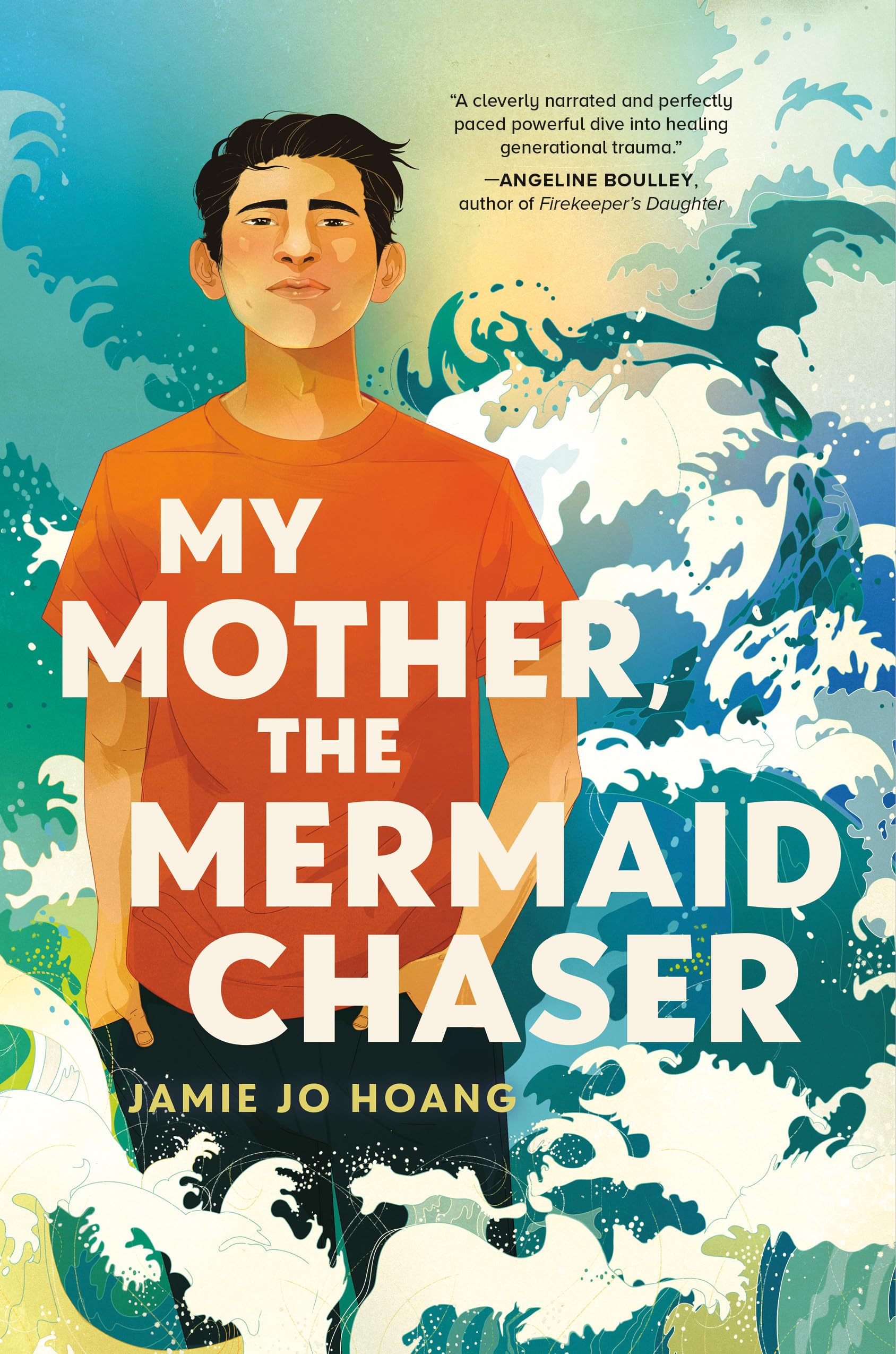

I had the privilege and pleasure of connecting with acclaimed Vietnamese-American author Jamie Jo Hoang in anticipation of the release of her stand-alone companion book, My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser, out September 23rd of this year.

2025 marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. In the spirit of reflection, Hoang’s novel is deeply rooted in her family’s history, inviting readers to consider the long reach of war. The trauma of loss, grief, and resilience, and Hoang’s writing travel beyond those who survive through war to encompass the children who are born in its shadow.

Told in dual points of view and timelines that span decades, My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser explores how to make sense and reclaim a fractured, tumultuous past to usher in a present marked by confidence and peace.

Before My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser hits shelves this fall, be sure to check out Hoang’s debut young adult novel, My Father, the Panda Killer, which was an NPR Best of the Year 2023 selection and featured on The New York Times, Distractify, Houston Matters (Houston NPR), and more.

…as well as, of course, our conversation below!

CAITLIN TAYLOR SO: In your personal essay in Salon, you discover writing as a tool to unpack who you are (as a Vietnamese person) and how you view the world around you. How did your writing and journey to self-discovery lead you to writing My Father, the Panda Killer and now My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser?

In writing these two books, how has your relationship to writing and to yourself (as a Vietnamese person) changed or evolved?

JAMIE JO HOANG: Similar to Jane, I spent a lot of time hiding from or outright denying my “Vietnamese-ness.” I was embarrassed by everything that made me stand out. I threw away my lunch at school. I told my parents my pick-up time was ten minutes after it was, so no one would see the beat-up cars we drove. I excelled in school to prove I wasn’t “too Vietnamese.” At the same time, I was keenly aware of the sacrifices my parents were making so that I could have a better life.

My Father, the Panda Killer was initially called Jane for President. It was about a Vietnamese girl going to an elite prep school and trying to fit in. It was the story I wanted to live. But it wasn’t real. Then one day, as I was poking around in my archives, I found this essay I had written on a writing retreat with some friends. It was a fictional piece based on a photo taken during the Vietnam War. In the picture was a little boy, maybe 7, curled up next to his baby sister, who lay in the most protective space the boy could find—a cardboard box. My parents were children during the war. This child could’ve easily been my dad. This image was one of many beginnings to My Father, the Panda Killer.

Credit: Chuck Harrity

As for my relationship with writing and myself, I think it’s still evolving. I’m still unlearning, learning, and discovering fresh ways to understand who I am as well as who I want to become.

CTS: Can you delve into your research process as you began writing My Father, the Panda Killer and My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser? What was your experience learning about Vietnam’s history and, by extension, your family’s history, prior to when you planned to write these books, and how did this background knowledge (or the lack thereof) inform your future approach to further research?

JJH: Researching the Vietnam War was frustrating. Most of what I found focused on the American experience—especially soldiers—and barely mentioned people like my family. Even the few Vietnamese perspectives I came across didn’t reflect the stories I’d grown up hearing. The diaspora is incredibly diverse, and I couldn’t read Vietnamese well, which made it even more challenging.

I spent a considerable amount of time listening to interviews from the UCI Vietnamese American Oral History Project and hearing stories from other refugee families. That archive was invaluable while I was writing.

Later, I connected with two outstanding scholars: Dr. Nu-Anh Tran from the University of Connecticut and Dr. Quan Tran from Yale. They helped ground my story in historical facts and gave me evidence for things I had sensed but couldn’t prove—like how someone from South Vietnam might defect to the North.

For My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser, I also leaned on my sister, Dr. Kimberly Kay Hoang, whose research in Vietnam added so much depth. Dr. Nu-Anh Tran and Dr. Quan Tran have both translated Vietnamese texts into English, which helped open an emotional door into a past I hadn’t been able to access before.

CTS: In your article in TIME, you grapple with the fact that “Viet Joy is not yet a concept in motion.” Last year, I watched a documentary called New Wave, directed by Elizabeth Ai, about the world of 80s Vietnamese new wave. Watching it made me truly realize the lack of Vietnamese diasporic stories that center joy and community when so many have instead centered trauma and separation.

The inclusion of Paris by Night in the documentary also helped me recognize the instances of Viet Joy in my own life: staying over at my grandparents’ house and Paris by Night being a constant on the TV, for example.

In writing and researching for My Father, the Panda Killer and now My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser, how did you set out to prioritize moments of Viet Joy in your books and balance them with very real and difficult portrayals of PTSD and trauma? In doing so, how have you been able to recognize Viet Joy in your own past and present?

JJH: Oh my gosh, I grew up on Vietnamese New Wave! My older cousins were part of that whole scene. But I’ll admit—when I was younger, I used to cringe at it. I saw the singers and dancers as knock-offs of American pop stars. That’s what happens when you grow up trying so hard to assimilate. If white kids were doing it, it was cool. But if Vietnamese people did the same thing? I felt embarrassed. I could honestly shake my younger self now.

That’s why I love the New Wave documentary so much—it centers Vietnamese creativity and joy, and shows how rich and complex our diaspora really is. It took me years to appreciate that, but now I feel so proud. I hope other Vietnamese folks feel that pride, too.

For my books, they’re set in very real times of struggle for me, but like life, nothing exists in a vacuum, and I believe that whether I recognized the Viet Joy at the time or not, it definitely existed. I know this because there’s no way I would’ve made this U-turn back to my roots had there not been moments of joy in my life. For me, to zigzag through trauma and then live in the pursuit of joy–that’s the definition of resilience. The path is not linear, it sometimes squiggles in confusing ways, but that steadfast resoluteness, to not become the thing that hurt you, is what I admire most about our Vietnamese people. It’s proof that love is stronger than hate.

I also hope that my books serve as a reminder to people that there is a real human toll in war. There is a cost to our bodies, our hearts and our soul; and its highest price is paid for by civilians.

CTS: Illustrating the life-long effects of generational trauma through a dual timeline story is a powerful creative decision and also one that makes a lot of sense. Can you tell me a bit about your process in figuring out when and where to set these two timelines for both My Father, the Panda Killer, and My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser, as well as the process in writing through them?

Did you know the ending for each timeline and work your way backwards? Did you often switch between the two when writing, or was it when you were writing for Jane and Paul, you were only writing for Jane and Paul, and when you were writing for Phúc and Ngọc Lan, you were only writing for Phúc and Ngọc Lan?

JJH: I wish I were that organized! I never write with an outline or a clear ending in mind—not for lack of trying. I used to make outlines and even taped them next to my computer to stay on track. But the story always veered off course, usually before I even got to the second bullet point. Eventually, I came to accept that the unknown is an inherent part of my process. I’ve learned to trust the story and let it lead.

I chose the timelines because they were closest to my own experience, and I wanted to center a fully second-gen Vietnamese voice. As for the dual narratives—those were a bit chaotic at first. The first draft was nothing more than 200 disjointed scenes split between the two characters. Once I was about 75% through the draft, I wrote each scene on a note card, laid them all out on the floor, and started rearranging them where I thought key moments from each character could intertwine. That’s when I began shaping the scenes into the larger narrative and character arcs.

CTS: Did you know when writing and publishing My Father, the Panda Killer that you would plan to write and now publish My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser as a companion piece? What is it about the dichotomy between father and daughter and mother and son that allows for such rich storytelling and offers an opportunity to explore so many themes?

JJH: You’d think I had both books planned from the start since they sold as a two-book deal—but honestly, I had no idea My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser would even exist until I found myself pitching it out loud during my first meeting with my editor, Phoebe Yeh. Initially, I was just going to add a short epilogue in Paul’s voice to wrap things up and close the book on this family. I didn’t realize how much more there was to unpack.

I’m the second oldest of four siblings, so even though people (including my own family) think Jane is me and Paul is based on one of my younger siblings, the truth is—they’re both drawn from different parts of my own experience. I’ve felt both the protection and abandonment of an older sibling, and I’ve also been the protector and abandoner of my younger ones.

Writing My Father, the Panda Killer was emotionally exhausting, so the idea of going back into this family’s story felt punishing—like mom made me eat raw red chili peppers, punishing. I knew the burn wouldn’t just hit my mouth; it’d twist in my gut. That’s because, for me, the physical abuse in My Father, the Panda Killer was easier to face than the emotional neglect I’d have to confront in My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser.

At the heart of it, these books aren’t really about father-daughter or mother-son relationships—they’re about the complexity of being a child of parents who were deeply traumatized and the different ways all of us try to survive that. With My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser, I wanted to show female fortitude alongside the character’s immense suffering.

CTS: I’m the daughter and granddaughter of Vietnamese refugees myself. My mom was born in Sài Gòn in 1972 and fled to France with my aunts and grandparents, and eventually ended up in New York in 1981. Growing up, my grandfather would tell me stories about the Vietnam War, oftentimes singular experiences that he had, and I worked on trying to connect these experiences as best as I could in a personal essay titled “Luck is a Funny Thing.” I intentionally retold these experiences from my perspective, however, because I didn’t feel confident in embodying my grandpa’s voice or story.

Can you tell me what went into your preparation to write Phúc and Ngọc Lan’s respective stories? How did you go about determining their distinct voices, and how much inspiration did you draw from members of your own family?

JJH: Yes! I loved the fragmented way you told each chapter of your grandpa’s life. Your grandfather was cunning, just like so many Vietnamese people had to be. Almost every story I’ve heard has a moment of clever deception or some quick thinking that helped someone escape danger. I’ve always been fascinated by how ID documents during the war were both essential and incredibly risky—something meant to protect you could also get you killed.

Part of why I start both of my books with the bold statement: “This book is NOT a history lesson,” is to remind readers that these stories come from a second-gen perspective. Like you, I didn’t always feel confident telling my parents’ stories—especially because there are writers from their generation who are already doing that, and doing it beautifully. But just because my books are fiction, it doesn’t mean they’re any less real; they’re grounded in honest emotions and truths I’ve grown up with.

I told Phúc and Ngọc Lan’s stories through Jane and Paul’s voices because that’s how I’ve always understood them—filtered through the lens of my own experience. During the writing process, I’d come up with a scene and then call my mom to check the details. For example, when I was writing about life on Kuku Island, I asked her, “What did you eat?” She said, “Nothing—we were starving.” I pushed back: “You must’ve eaten something; you were there for a year—and you survived.” She thought for a second and finally said, “Coconuts. There were a lot of coconuts on the island.” I waited for more, but she stopped there.

So I kept nudging: “Coconuts and…?” That’s how most of our conversations went—she’d toss me breadcrumbs, and I’d keep pecking. Eventually, she shared stories about herbalists and fishermen on the island who helped by sharing what they gathered or caught. But when it came to the traumatic stuff, I never pressed. I don’t believe it is my place to force my parents to have to relive things they’d rather forget. That’s why my work could never exist as anything but fiction.

CTS: I chuckled at the notes you included under Chapter 4, Chapter 13, and Chapter 14, and then the footnotes in Chapters 24 and 34. I also grew up recognizing 4 as an unlucky number from my dad’s Chinese side and my mom’s Vietnamese side. I’m curious about your reasoning behind including the chapter numbers. Did you do so knowing you were going to call these specific numbers out?

I saw these asides as creative, tongue-in-cheek moments where I, as the reader, could see the ways you, as the author, were subtly and unapologetically Vietnamese and Asian. What are some other characteristics and habits you embrace and practice in your day-to-day that you would tie to your Vietnamese and Asian identity?

JJH: One of my all-time favorite books is House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. What I loved most were the footnotes—they weren’t just side notes; they were like little clues or keys woven into the story itself. They felt like part of the narrative, not just extra info. I knew I’d need some footnotes in my book to help bridge language gaps, but I also wanted them to be something fun—like little surprises readers could look forward to in the smaller text.

As for the “unlucky numbers,” I remember noticing they were skipped on elevators in Vietnam. Then I started hearing stories about people changing their phone numbers or avoiding certain house addresses because of bad luck. It’s one of those cultural quirks I’ve grown to really love. Even some of the most devout Catholics I know visit a soothsayer once a year. Those kinds of contradictions are what I love exploring in my stories—flawed, complex humans who deserve empathy and compassion.

As a daily practice, I am learning to read in Vietnamese. My son is 4 and I want him to know our language, so I buy bilingual books which I have to pre-learn before I can read them to him. In a way, my mom and I have flip-flopped. She’s reading The Cat in the Hat to try to get to the point where she can read my work, and I’m reading Rainbow Fish to grow my Vietnamese literacy. I think it’s quite humbling for both of us.

CTS: What can readers expect from you next after My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser?

JJH: When I figure it out, I’ll let you know! Just kidding, sort of. I’m working on another young adult novel, set in present day and involves Vietnamese hip-hop and dance. As a “non-outlining author” the full trajectory and themes haven’t appeared yet, but I can say that I’m really excited to be leaning deeper into Viet Joy with this next book.

CTS: And just for fun, what’s your favorite Vietnamese dish?

JJH: Do I have to pick one? For a meal: bún thịt nướng (pork vermicelli). Snack: xôi (sticky rice) Drink: rau má (pennywort drink).

***

Jamie Jo Hoang is the daughter of Vietnamese refugees. She grew up in Orange County, CA—not the rich part—and worked as a docuseries producer before shifting to writing full-time. Her debut young adult novel, My Father, The Panda Killer, was named one of NPR’s Books We Love and received an Honorable Mention from the Freeman Book Awards. Hoang is also the author of the award-winning adult novel Blue Sun, Yellow Sky, which was named one of the best books of the year by Kirkus Reviews and won a silver medal at the Independent Publishers Awards. Her work has been published in TIME, SALON, and Tiny Buddha. When she’s not writing, Hoang loves to take long walks, travel, and scuba dive. She lives in a house covered in Post-It Notes with her husband and son.

Preorder My Mother, the Mermaid Chaser here.

Born and raised in Queens, Caitlin Taylor So is a Chinese-Vietnamese writer who is passionate about prioritizing and amplifying marginalized voices. She graduated from Emerson College with a degree in publishing and marketing. Her writing can be found on Business Insider, PopSugar, WebMD, Medscape, The New Absurdist, and Her Campus Media.