Here is the son of a helium baron. His head is a mylar balloon, lolling above his polo shirt collar. The collar a green piqué. The shirt striped in navy and white.

Here is the house that helium built, floating sixty feet up in the sky. A complex system of three thousand ropes tethers it to the ground. Nothing grows beneath this house other than mushrooms and mice.

The son of the helium baron lives with his father and stepmother here in the house that helium built. The stepmother has a small human head. The stepmother was once the son’s nanny, and she tends to him with the care she has employed since his youth. Each morning, she refills his head using a gold-tipped nozzle designed especially for this purpose. She inserts the nozzle into his valve and wraps her fingers to create an airtight seal.

Before he was born, the helium baron’s son might have had another name, but for his twenty-six years, everyone has called him Bob.

Here is Bob, the helium baron’s son, with a mylar balloon for a head.

* * * *

Mylar was invented in 1953. In ’64, to assert scientific dominance over the Kremlin, NASA launched a mylar balloon 100 feet in diameter into darkest outer space. Bob’s mylar balloon head is eighteen inches in diameter. Bob’s balloon head has never left his house.

Bob is a performance artist and a prankster, and for the years leading up to his father’s death, he has occupied himself by mounting intricate artistic pranks with volunteers recruited from Craigslist. Bob’s many performance pieces recast human bodies as furniture, as distance and idea. Bob could burst with longing for the outside world. His art is his hand reaching out across space.

Here is Bob’s sticky red heart, thumping as one might expect a human heart to do, metaphoric home of Bob’s immense emotional range.

Here is Bob’s mylar balloon head, byproduct of his country’s craving to win, billowing up from a hard plastic valve at the base.

Archimedes’s principle of buoyancy: Every body displaces air equal to its own volume, simply by asserting its existence.

* * * *

In 1918, the helium baron’s grandfather built a large house on land hiding natural helium reserves. At once, the voices of the family (who had human heads, all) began to rise in pitch; the house upheaved from its moorings. Panic over a blimp war with the USSR transformed the family into magnates. They tethered their house to the ground and embraced their tiny voices as accoutrements of wealth. For 100 years, the family creaked around the house that helium built, held aloft by ambition and the mysteries of space.

For years before his father died, Bob bunkered in the darkest room of this house before a wall-sized TV, watching with grave attention the half-minute delayed video stream from each performance prank he mounted. Bob has never met his pranksters, nor watched his art in person, but Bob’s air head can hold the memory of every prankster and his sticky red hope for every one of his pranks. Here is Bob, a balloon for a head, who understands better than you every meaning of vacuum.

* * * *

The helium baron, who had ― above all ― wanted a son with a human head, died from an asthma attack. The helium baron didn’t know he had wanted this until he was given something else altogether.

The helium baron’s asthma attack occurred during a dinner party in the house that helium built. The guests ascended to the house much as one climbs into an airplane, on clanging metal steps not wide enough for an average human foot. Dinner was unpalatable, an experiment in saltless cuisine ― stringy, undercooked squab that got caught between the teeth of the guests.

Here is Bob, who eats nothing but helium, whose faceless balloon head has no teeth at all, whose favorite sensation is his stepmother’s fingers wrapped around his valve each day.

* * * *

Bob’s shiny Mylar balloon head presents distorted reflections of everything that surrounds him. Each morning, his stepmother wraps her fingers where nozzle meets valve and tries not to stare at the wilted reflection of herself that grows smoother as Bob’s head fills taut. She sees how her nose becomes prominent; she pities herself for having a big nose. Bob watches her watching him, and it’s the closest he’s felt to someone looking him in the eyes.

Here is Bob, sitting before the wall-sized TV, specially designed not to shimmer with the glare of Bob’s balloon head, the pranksters’ images reflected on both sides of his head in moving muted color. Here is Bob, straining to hear the video over his thudding red heart, of the prank that inspires it all.

Bob has a dark sense of humor and a rush for exploring what binds us. Because Bob, in his vacuum, stands unbound, untethered, ununited in his oddity; here is Bob with his human feet that have never touched the earth.

* * * *

Archimedes’s principle of buoyancy: when a body is less dense than the air it displaces, it will float.

* * * *

The video playing on Bob’s wall-sized TV — the video that inspired the prank that ended his father’s life — showed sixty-three people descending upon Boston’s South Station with hollow disco balls over their human heads. As Bob’s vision blurred, the roving disco ball heads unified among the disparate human-headed crowd — they became a giant mirror shattered to the ground; they became a single, shifting constellation against a swirling multi-hued sky.

If only Bob could reach out to this moment, finger the shards of mirror glass across distance and the half-minute delay.

But unlike Bob, who can see just fine, the pranksters with disco ball heads couldn’t see a blessed thing. The pranksters in the disco balls felt trapped in darkest inner space, set apart from everything but themselves. Alone in their heads, the disco-ball pranksters knocked and fell sideways into the kiosks and tables, and a third-year doctoral student in Victorian art tumbled down an escalator and shattered his left patella.

* * * *

When the helium baron turned forty years old, he drifted unmarried and unlegacied in the cavernous house that helium built. The helium baron’s voice had long since risen to a permanently squeaky timbre, and he’d been saddled with asthma and acid reflux as a result. The helium baron had little hope for finding a wife who could abide him whisper-wheeze-squeaking her name. Here is the helium baron, heartburned and heavyhearted and floating sixty feet above the ground.

The helium baron found a surrogate and an egg donor and set about creating a family. He named the boy after himself, but at the first sight of Bob, the helium baron lost his grip on the blue balloon bouquet and shrank into silence and grief.

For the rest of his life, the helium baron inhabited that moment. Every instance of love and respect he offered was overlaid by shame. He hired a nanny from the local party store, and he indulged Bob’s desire for gadgets to support his art. He locked himself in his study at night, poring over family medical histories, alone.

Bob, the helium baron’s son, knew of his father’s disappointment. You try living with a mylar balloon head and remaining ignorant to the melancholy of your family. Here is Bob, holding tight to an excruciating hope that his helium baron father will someday, someday, rise above.

* * * *

The saltless squab at the dinner party was on account of the acid reflux. The helium baron’s personal physician had recommended the change in diet. The physician, among the dinner guests on the night of the helium baron’s death, picked stringy squab out of his teeth and regretted that his advice had come two days before the party rather than two days after.

Of course, the physician’s advice could not have come two days after the dinner party, as the physician will already be on television, explaining the intricacies of asthma attacks: After wheezing comes silence, and silence ends it all.

* * * *

Bob stands before the bathroom mirror, reflecting his head, reflecting the mirror, reflecting his head, reflecting the mirror, and leans his hands on the cool marble sink. He wishes for the chance to see one of his pranks in person, wishes for the breath of another someone on the spot where his neck might have been, wishes for anything except a human head, a high-minded father, or a life lived outside this swaying old house. Here is Bob, the helium baron’s son, who has learned better than you the futility of wishful thinking.

* * * *

Bob is twenty-six the evening his father dies. How much longer before his seams disintegrate too far to be patched; how much longer before his valve is too worn from use? In the evenings, Bob drifts to sleep alone, and in the mornings, he wakes wilted and dreary and with a feeling that someone other than Bob might describe as light-headed. His stepmother enters after a staccato tap-tap on the door; she kneels beside his bed, still in her nightgown, and wraps her calloused fingers around his valve as she inserts the nozzle to create a good seal. Here is Bob’s stepmother, on her knees in her nightgown before her grown stepson, calculating how much longer this aging balloon can hold invisible helium particles. Here is Bob’s stepmother, wondering how long this vacuum will last.

Bob’s stepmother walked to the bathroom each morning after refilling her stepson’s head and looked at her nose in the mirror. Bob’s stepmother is called Emily. She will be a widow at forty-five and has been the sole caretaker for her stepson for his twenty-six years. The helium baron excels at telegraphing affection from behind a financial report. After his death, Emily will miss her husband’s distracted caresses, miss human contact that meets no practical need. She will miss the feeling of an unsure life displaced by something fantastical. She will miss a world where terrible things could be blamed on terrible people.

Archimedes’s principle of buoyancy: what is heavy moves aside so that the lighter body may rise.

* * * *

Until the birth of his son, the helium baron’s vision of his family’s commodities had little to do with levity or balloons. In the helium baron’s head, helium meant airships and magnets and fractional distillation. In the helium baron’s head, helium meant wealth, acid reflux, the mantle of familial fate. After Bob was born with his mylar balloon noggin, the subject of helium weighed heavily on the helium baron’s mind.

One night, after reading again through the egg donor’s medical records and with a vinegar tightness rising at his throat, the helium baron staggered into his two-year-old son’s bedroom with one of Bob’s thick markers tight in his fist. Trembling and silent as he wept, the helium baron leaned over his sleeping son’s balloon head, nested in piqué knit blankets of darkest midnight blue. He wrapped his fingers tight around the valve to create a steady surface and drew with wavering lines: two eyes, one nose, one mouth, two ears. In the reflective plane of Bob’s balloon head, the helium baron watched himself cry as he desecrated his son, his dripping tears streaking the face he had drawn. Here is the weeping helium baron, bronchioles closing and beginning to wheeze. Here is the wheezing helium baron, witness to himself on his knees before his son, a water-soluble marker clasped in his human hand.

* * * *

Emily, the helium baron’s wife, was born severely hard of hearing and spent her youth wearing specially designed hearing aids in both ears. When she was small, her mother would crawl into her bedroom each morning and sit on her knees beside Emily’s bed to nestle the hearing aids into her head. When Emily was twelve, she received a cochlear implant and was forced to relearn how to hear. Her parents took her out of the Deaf school; the language of her body atrophied from neglect. She missed her community of intimates, missed seeing herself mirrored in others’ hands.

After the implant, all around her, people sounded as though they had laryngitis; Emily matched them by speaking in whispers and sighs. When she met the helium baron at the age of nineteen, she did not hear the high-pitched squeak that others did. The helium baron entered the party store where Emily worked and started falling in love with her on the spot; it was as though she had been designed especially for him.

Here is Emily, fixed despite never having been broken, staring at herself in the bathroom mirror and turning on the cochlear transmitter that curves around the back of her ear. The soon-to-be-widow is staring at her nose. Bob’s art and Bob’s life give Emily feelings that she can only express with her old voice, and with her hands, she says these words to herself in the mirror.

When her fingertips touc,h she is reminded of the labored callouses on her fingers. Emily wonders if there is anything for her outside this vacuum-sealed life of service and doubt.

* * * *

The helium baron was kind to his wife and his son, but he was not a mirthful person. He was serious about being taken seriously and devoted tremendous energy to the cause. The helium baron worshipped gravitas; he inflated himself with trappings of grandeur and held himself as apart from his colleagues as technology would allow. He couldn’t square Bob’s pranks with his vision of himself, but wouldn’t have dared interfere. The helium baron never stopped fearing he might not love Bob the way that he ought.

Bob declined his father’s invitation to the dinner party, and the helium baron was devastated by his own relief.

* * * *

The night that Bob kills his father with an elaborate prank, the unsalted squab is served with steamed mushrooms and roasted potatoes. There is no butter on the table. Few of the dinner guests will remember to include this detail when prevailed upon to tell the story of the evening that they ate gamey squab and witnessed the helium baron die.

Under the personal physician’s orders, cake and champagne were to be displaced by celebratory sugar-free mango frozen yogurt, a concoction designed especially for the evening.

The helium baron is in a state of prolonged agitation about the dinner party. An order was placed with a silversmith for a specially cast single place setting, three-quarters the size of average silverware, to enlarge the appearance of the helium baron’s average-sized hands. A slightly higher-than-normal dining chair has been situated at the head of the table. A large mirror has been hung at the end of the dining room, canted at an angle to distort the helium baron’s reflection and present him as larger than life. Russian blue tapestries hang along the walls to dampen the echo of the helium baron’s cartoon mouse voice.

Bob, built around a noble gas, has a surprisingly average-pitched voice and uses it to laugh as frequently as he can; he has trained himself to laugh even when he ought to weep. Here is Bob, who will be haunted for years by the fact that, so help him, the night he killed his father with an elaborate prank, he laughed.

* * * *

Other than the helium baron’s wife and the dinner guests, virtually no one new has entered the house since Bob was born. Here is the house that helium built: floating sixty feet above the earth, tethered to the ground over a shadow forest of mushrooms and mice, a lonesome fortress in the sky. Here is the house in which the helium baron died: inhabited soon by the only two remaining members of his family, knocking around together and apart.

After the helium baron’s death, Bob and Emily will decline television interviews; they will decline to speak to one another as well, and will come together only in the mornings when Emily refills Bob’s wilting head. For years, they will send search parties after the right words, but everyone will turn up empty-handed.

* * * *

On the night of the prank that kills his father, Bob lurks in the darkest inner shadows of the tapestries on the dining room walls, waiting for the helium baron to begin his speech. A parade of seven waiters rounds the table and replaces the half-eaten plates of squab with bright, silver-domed platters. The waiters stand with hands poised on the silver dome handles. The dinner guests make use of their distorted reflections to extract strings of squab from between their teeth.

The helium baron clears his throat and dings his miniature spoon against his water goblet. He thanks his guests for the favor of their attendance. The helium baron raises his glass, and across the room, a larger version of the helium baron raises a larger glass.

* * * *

Before his father died, Bob watched the video footage of his disco ball prank and the images of his fellow pranksters, unified with their glittering heads, reflected spectacularly on Bob’s mylar balloon head. No one was there to see them.

* * * *

The helium baron raises his glass. Helium is a noble gas, he says. It is the gift that built this company, that built this house. Helium may be number two on the periodic table, but it will always be number one in our hearts. Here is to what binds us. Here is to another century of ambition and helium and wealth. Here is to health and to sugar-free mango frozen yogurt.

The waiters prepare to lift the silver domes in unison, revealing Bob’s elaborate prank.

The helium baron raises his glass even further. Bob — who for twenty-four years has shuddered to sleep with the memory of his father’s marker sliding across his balloon head — gives the signal.

The only way to go is up, the helium baron says. The waiters lift the domes.

* * * *

Days earlier, watching his wall-sized TV, Bob cried out in despair when he saw the third-year doctoral student tumble down the escalator, disco-ball headfirst. But despite his smashed kneecap, the student did not gasp in pain.

The student pulled up on the dented disco ball and revealed his human head. He rapped his knuckles on the disco ball and tossed it into the air. Did you see that, he shouted. Did you see? This disco ball just saved my life. And he laughed. And he laughed and tossed the disco ball into the air until the ambulance arrived, and the video ended with a click.

* * * *

At the dinner party that kills him, the helium baron lifts his glass even higher, and the canted mirror above the dining table towers over them all. The only way to go is up, he says. The waiters lift the bright silver domes all at once. The helium baron’s son steps out of the tapestried shadows.

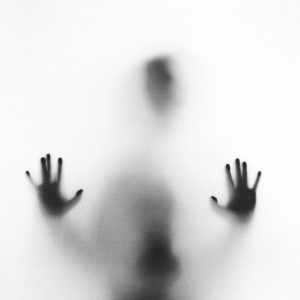

Here is Bob, standing in front of the Russian blue tapestry, looking for all the world like a mylar balloon launched into darkest outer space.

* * * *

Up go the silver domes to reveal no sugar-free mango frozen yogurt concocted especially for the occasion.

Up, instead, go mylar balloons, tethered to dessert platters with very short strings.

Up goes the helium in the balloons, bobbing to a floating rest at exactly the height of the dinner guests’ heads.

* * * *

Pause here with Bob in the carefully constructed scene in the dining room, for Bob is nothing if not meticulous. Slip into the still moment that Bob will revisit for the rest of his life, however long that may be: the helium baron, small and human and standing before his Russian blue tapestry, glass raised in an unmet toast. Before the helium baron, a table full of dinner guests whose human heads have been obscured — displaced — by mylar balloons, reflecting back each other and the tiny, warped image of the helium baron. Bob, yoked by the risk that his prank will fall flat, that his father will never forgive him for making him ridiculous and small, scrutinizing the liminal expression on his father’s face, precursor to confusion, horror, or — here Bob hopes — joy.

A moment in which the tight corset of control around the helium baron’s chest is just about to spring.

This frozen moment cannot last, of course.

* * * *

Up goes the helium in the balloons, bobbing to a floating rest at exactly the height of the dinner guests’ heads.

Down goes the helium baron, father of a beloved, balloon-headed son, surrounded by dinner guests with sudden-onset mylar balloon heads.

Archimedes’s principle of buoyancy: set apart by difference from all that surrounds it, a body is going to rise.

Here is the helium baron, in the floating house that helium built, voice so high that it’s given him asthma, set apart in a room where he alone lacks a mylar balloon for a head.

Here is the helium baron, gravitas punctured by a noble gas, falling against the back of his specially designed, extra-high chair, deflated.

On account of the rumors about the helium baron’s son, the dinner guests are reluctant to mention the Mylar balloons tapping gently against their noses. Fingernails between their teeth, they hear something that sounds like a forgotten tea kettle, like a rubber balloon with a leak.

Here is the helium baron at his dreaded dinner party, who for twenty-six years has lived with unfathomable love and regret for his son, awash in the unexpected relief of his greatest nightmare, leaning into the back of his specially designed chair, whistling like a forgotten tea kettle as he laughs for the first time since childhood.

A body will rise.

Here is Bob, grateful and alive, laughing alongside his father, the son and the father looking at each other and at the large canted mirror and seeing reflected back a constellation of mylar balloons cast into relief against a swirling Russian blue sky.

Here is to what binds us.

For a full thirty seconds, the helium baron’s laughter rolls and rises in the dining room, raised by the weight of all that it has displaced.

Here is Bob, days before his father’s death, his sticky red hopes buoyed by a brand new idea. Bob laughs with the disco ball as it’s tossed in the air. What sets us apart makes us rise. Here is Bob in the dining room, laughing and laughing alongside his dad, hearing not wheezes but delight.

Emily cannot see the helium baron’s twitching hands; she can see just her nose reflected as she does every day. She knows Bob’s art and knows her husband’s weakness, and suspects this will come to no good. She has turned off the transmitter that curves around her ear and talks to herself in her almost-forgotten voice, her movements hidden from view by the cacophony of balloons. Here is the nearly-widowed Emily, finding a momentary balm in shouting at strangers who cannot see to hear.

Witnessing his art for the first time in his life, Bob looks into the mirror and sees not a reflection reflecting a reflection reflecting a reflection, but a textured landscape of all that surrounds him. He, whose vacuum would surely set him always apart, sees himself as part of a unified idea: the unbreakable oddity of father and son.

Here in the big canted mirror, everything happens in reverse: rather than a living helium baron floating toward death on his laughter, Bob sees a man brought to life.