As she floated near the viewport of the Nautilus IV for the fourth day, Faye stared out at what looked like a giant sleep-deprived but pupil-less eye. In actuality, orange-red lines haphazardly scored the white surface of the moon. She had first seen pictures of Europa right after she turned ten in 2230—the same year she had arrived at the Institute. For more than half of her life, the eye of Europa had been staring at her. Over the last twelve years, she had stared back, eagerly anticipating their face-to-face meeting. She first met her digitally in early classrooms, zooming in on discolored bands and on dark spots that marked those rare times when the surface ice melted for a brief moment. Later, she saw Europa live—or as close to it as one could get from Earth. She and her classmates would take turns peering through the curved mirrors of a high-powered telescope. Four days ago, the ship had slipped into its final orbit, and she and Europa were finally face to face. Three days ago, they launched the first test probe. And, two days ago, they launched a second (unscheduled) probe. Today, they floated, and they waited.

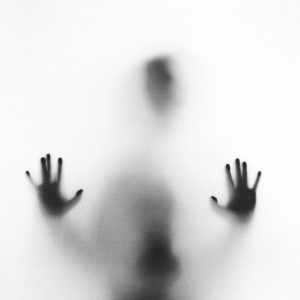

Though the crew had been told by the scientists that the reddish bands were ice-mixed hydrated salts as well as potentially magnesium sulfate and sulfuric acids, Faye and her companions had spent hours—days even—on the trip gleefully coming up with better explanations. Maybe Europa was just tired, maybe she had too many beers the night before, maybe she spent too much time in a chlorinated pool, or maybe she was just really, really high. Faye never shared her personal theory with her crew. She thought it looked like she had been crying. That possibility comforted Faye, and she felt that if she could just make it to Europa, her life would change. Europa would welcome her and comfort her. All the pain would be gone: the pain of losing Tommy, the pain of being taken from her family, the pain of the surgeries, and the pain of living on a dying planet. Now, looking down and waiting, Faye couldn’t shake the feeling that Europa wasn’t sad or tired or hungover. She was angry.

A gentle pressure nudged the water along her shoulder blade a moment before fingers squeezed the soft flesh between her neck and the bony joint of her shoulder.

“Shit, you scared me,” Faye said as she spun around to face Jake, one of her shipmates. “Don’t sneak up on me like that!” Her voice transmitted from the sensor attached to her throat to the bone conduction implant which they all wore.

Jake, who had come from an encampment near Phoenix, gave her a wolfish grin, “Staring into her bloodshot eye again, Huck?” She punched him lightly on the shoulder. In their watery environment, Jake’s shoulder-length brown hair fanned out around his head, and his dark eyes twinkled.

“I guess…” she said. Her voice trailed off before revving back to life: “I’m worried, Jake. We should have transitioned into the descent module yesterday—even with the unscheduled second probe.”

“Ah, you know how the labbies get when they get new data,” Jake said. “They’ll come up for air—pun intended—and send us instructions soon.” Jake grinned.

“I don’t know,” she replied, turning back to look at Europa.

“Listen, I know you like to worry but we’ll be splashing around in Europa in no time,” Jake said. His smile faded a little as he recognized that Faye was not convinced. He tried again, “You know, you’ll never win a staring contest.”

When Faye rolled her eyes, Jake gave up. He kicked off the wall, propelling himself down the tube toward the common room and said, “Lunch in five.”

Turning back toward Europa, she raised her fist to the view port and opened it, palm up. As her fingers uncurled, a small plastic horse, tethered to her middle finger where the webbing stopped, drifted up in front of her. Icy pin pricks raced up the bones in her legs, up her spine, and then down her arm and out to her fingertips. It was a feeling she knew too well.

###

At the encampment south of Houston, ten-year old Faye snuck away, as she had on many previous days, from the haphazard arrangement of faded green canvas tents to watch the brown water of the Brazos River slowly meander by. It wasn’t the brownness that captivated her. Rather it was the other colors: shining swirling rainbows, long streaks of bright blue, orange or red, and the many-colored plastics that sometimes got caught in the grasses near the shore. Faye stayed out of the water not because of her mother’s repeated warnings, but because of Tommy.

Tommy had been her best friend in the encampment. His sandy brown hair, overly tanned skin, and sparkling blue eyes reminded her of the river itself. It had been Tommy’s idea to wade into the shallows and retrieve a bright purple toy horse he thought she would like. She reminded him that they were told to stay out of the river, but he just waved his hand dismissively as he approached the edge. The tiny toy horse had lodged itself in some reeds about three feet from dry land. Tommy waded out, grabbed it, and immediately started retreating toward the bank, high stepping the whole way. Faye laughed, assuming that he was clowning around. However, as he emerged from the water, he started crying—something she had never seen Tommy do. He frantically rubbed dirt on his legs to clean them off. With fresh water a luxury in the encampment, they often used dust to clean themselves just like the sparrows and the robins. She tried to help him, but nothing worked. Instead, clear water seemed to seethe up from inside him and form painful bubbles on his skin. That night she heard Tommy crying in his family’s tent. After that, she didn’t hear him anymore. On the third day, Faye joined the community as they buried Tommy in the field to the south of the tents. So, no, she wouldn’t go in the water, but it still drew her. She still liked watching it drift by.

Tommy had also taught her how to catch doodlebugs in the soft dirt near the river and that was what she was doing today. She squatted, staring down at a number of small conical pits and set the purple horse down nearby. With her index finger, she lightly tapped the edge of a cone, knocking a bit of silt into the bottom. Tommy called this knocking on their door.

“Too much and they won’t answer; too little and they won’t hear you,” Tommy had told her.

She waited and watched the bottom. She heard her mom’s voice calling her but she could also hear Tommy’s voice, in her mind, telling her, “Guess this one’s not home.” She moved to the next cone to the left—this one was smaller but with sharper edges. She gave the dirt a tiny nudge. This time, a little sputter of dirt appeared at the bottom. She scooped her hand through the dirt, letting it sift through her fingers until the tiny doodlebug was scooting around in her cupped palm.

“Hello, there, Mr. Doodlebug,” she greeted him. He said nothing as he continued to scoot, looking for the edge. Her mom’s voice grew closer. She probably could have seen Faye now if it were not for the tall grasses surrounding her.

“It’s nice to meet you, but I better let you go. Mom is here, and she doesn’t like me being close to the river,” she said. “But, I promise I’ll come visit tomorrow.” She laid the back of her hand down on the ground and slowly tipped the small bug out. He immediately burrowed out of sight into the silt. Neither of them realized that she wouldn’t keep that promise. She brushed her hands off and stood up. She froze when she saw two pale men, wearing hats and long-sleeved brown coats to protect their skin from the sun.

“Honey, these men are from the…” Faye’s mom, Beth, said and looked at the taller of the two men. He looked at Faye, smiled, and said “The Institute for the Preservation of Humanity,” as if Faye would understand. She looked back to her mom for clarification. Her mom fiddled with her hands, one clutching the other.

“They, uh, want you to go with them,” she stammered, barely registering Faye’s presence as her eyes swept the river.

“Go where? Why?” Faye said. She stared intently at her mom who refused to meet her gaze.

“It’s ok. You’ll like it there,” the same man said and took a step toward her. Faye’s step back mirrored the man’s. She looked behind her, but the river offered no more sanctuary than her mother had.

“Faye Nichole. Stop,” her mother’s voice was stern and even. “You will do what I say and stop asking questions.” Faye looked at her mother in disbelief. Her mother looked directly back at her. Her eyes, streaked with red lines across the whites of her pupils, said what her words omitted and spoke of desperation, heartbreak and recent tears. She said quietly, “It’s for the best” and looked down blankly at the doodlebug village.

Faye felt a chill start up from her feet as if the ground had suddenly become ice. It raced up the bones of her legs and filled her chest. It rooted her in place as she stared at the top of her mother’s head, desperately hoping that she would raise her head, smile, and open her arms for a big hug. Instead, Faye flinched when the man’s hand touched her shoulder.

###

Day five of floating around Europa, found Faye back at the porthole staring out. Jake floated behind her chattering. Faye couldn’t tell if he was trying to distract her or alleviate his own boredom. Because Earth controlled most functions on the ship, the crew had nothing with which to occupy themselves. One can only spend so much time reading, playing games, or telling the same stories to the same eight people—especially eight people that had lived together for twelve years.

“Don’t you find it ironic that our Nautilus is filled with water and Captain Nemo’s Nautilus was surrounded by water?” Jake asked as if he hadn’t posed this question countless times already.

“Yes,” she said, “but it would be more ironic if our ship was surrounded by air instead of the vacuum of space.”

“Thanks to the Institute, we’d be just as dead. But, not forever,” Jake said, holding his index finger up to accentuate his point.

“You want to go back? To breathing air?” Faye asked, turning from the viewport to look at him.

“Are you kidding me? Back to normal and granted full citizenship?” Jake said. “What else would make up for the pain of those surgeries and all of the work of building the first habitats?”

“I don’t know. How many years will we have to build and maintain habitats before they can even perform those operations here?” Faye said, “Plus, I never thought I would feel this way, but I like the water. It feels like a never-ending hug.”

“All I know is that I am ready for some fresh water,” Jake said, shifting away from serious topics as he typically did, “I know what they said about the filters but thirteen months in here has made this water as musty as our dorm back on Earth.”

###

Faye took her first ride in a vehicle the day she left the encampment. The taller man, who had eventually introduced himself as Mr. Lewis, had guided her by the shoulder toward the waiting vehicle. Faye refused to turn around to see if her mother was watching her walk away. Part of Faye wanted to hurt her mother by leaving quietly, without crying, and without looking back. The other part of her feared that her mother had already headed back to the tents.

When the men came, kids left and never came back. It didn’t happen every day, but it happened enough. Their families suddenly received a few more rations and parents would often be selected first when day jobs in Houston became available. Some people dreamed of saving up enough to buy citizenship in Houston, but most accepted their fate in the encampment and spent what money they made on luxuries that made life a little more bearable—like the occasional piece of fresh fruit.

Faye marveled at the reflection of the sun off the surface of the vehicle, squinting her eyes as she approached. It reminded her of late afternoons when the sun seemed to light the river on fire. She touched the vehicle in wonder. The metal surface was smooth, hard, and warmed by the sun. Most of the metal Faye knew was pitted and scarred by rust. After a moment, a door slid up revealing four seats. Mr. Lewis extended his arm toward the vehicle palm up and looked at her.

“What?” Faye asked, after a few seconds.

“Please get in,” he said. Faye ducked her head and stepped into the darkened interior. She ran her hand along the surface of the seats. They were as smooth as the exterior metal but soft and cool to the touch. Mr. Lewis settled in next to her while the other man sat in one of the two chairs facing them. The earthy smell of a man not used to sweating mixed with the clean chemical smell of the interior filled her nostrils. The door slid closed, and they started forward with a lurch. The panels on all four sides of the boxy vehicle suddenly cleared, and she could see outside.

“Glass?” she asked, looking up at Mr. Lewis. She had seen glass before but never this much.

“Close enough,” he replied, trying to look kindly. Faye turned back and pressed her face to it. She watched as the tents passed and gave way to trees, burned out buildings, and then, more vegetation. She had switched places with the river. She now flowed by while the world stood still. Traveling across overgrown streets, she didn’t see another vehicle until the vehicle stopped at the base of a long, well-maintained ramp.

Without warning, the vehicle accelerated up the ramp toward what seemed like an endless and unbroken stream of vehicles. Just as she sharply inhaled and braced for a collision, a space opened and the vehicle moved seamlessly in between two large rectangular trucks. The world was moving too fast now, and it made her dizzy to look out of the windows at the passing landscape. So, she focused on the vehicle in front of her. A faded image of a young woman smiling and holding what looked like two rounded pieces of bread stared at her.

“What’s she holding?” she asked, pointing to the image. Mr. Lewis looked down at her with feigned surprise.

“You mean, you don’t know what a cheeseburger is?” he said smiling. “Well, that seems like the least we could do. Don’t you agree, Mr. King?” The man in front of her nodded and smiled at Faye, trying to look friendly but somehow failing.

“I think we can make that happen,” he said.

###

Later, she would recognize from their tone that they were repeating something that they had said before—like a scene that they had performed too many times or like Jake nattering on about the irony of water inthe ship. That recognition, however, was years away. Only ten minutes away, she bit into her first cheeseburger while Lewis and King looked on with amused smiles on their faces. As her teeth hit the patty at the center, saltiness flooded her mouth and grease trickled out of the corner of her lips. Lewis reached over and dabbed it with a napkin.

“Good, huh? See the Institute isn’t that bad. We have cheeseburgers,” he said, and both men laughed.

Lewis reached into his pocket and set a tiny purple plastic horse on the table. “I saw this on the ground near you when we met and thought it might be yours.” Faye’s hand snaked out quickly and grabbed the toy before quickly shoving it into her lap.

“Thanks,” she mumbled, making sure to keep her lips shut since there was still food in her mouth. King laughed, mouth open, giving the table a long and clear view of the partially chewed burger in his mouth. Lewis kept talking about the Institute, how it was going to save humanity, how she and other crew after testing and operations would be instrumental to that success by finding and building them new homes. He paused only to help her open a small packet containing ketchup. He used a lot of words she didn’t know so she quickly tuned him out and focused on eating.

###

She thought wistfully back to that cheeseburger as she grabbed the last remaining cylindrical tube from the rack. As soon as she removed her ENP—an enteral nutrition pack—the rack ascended back into the ceiling. It automatically descended three times a day and retreated after they had all claimed their meals. They had now been circling Europa for six days—three days past when they were scheduled to travel to the moon.

“Did you guys know that early space meals were flavored in an attempt to simulate traditional foods?” Jake asked, taking the cylinder out of his mouth and waving it around like a baton. Her shipmates, lounging at various locations around the circular central room, groaned almost in unison. Those days were long past. This cold—always cold—paste tasted of salt, algae, and assorted minerals. Not bad necessarily, just functional. Faye closed her eyes and ate her meal as slowly as she could. It was not a meal to savor, but there were only so many distractions on board the ship—making a meal last as long as possible was more about distraction than enjoyment. By the time she finished, the rest of the crew were all engrossed in their personal tablets, and Jake was gone.

She drifted down one of the spoke-like hallways. She found Jake at the communication console. As soon as he sensed her, he turned off the monitor and turned around. Before the screen went black, she noticed multiple messages from the ship with no response from Earth.

“What the…” Faye started until Jake quickly put his fist with thumb extended upward and tapped his lips twice—the sign for private. She gently tapped the implant near her ear, switching their audio to close proximity. Now, only implants within three feet would receive her transmissions.

“What the hell, Jake?” she whispered instinctively. “They aren’t answering messages either?”

He put his hands up, palms out. “Nothing to worry about. I am sure they are very busy. It just seems bad, because we aren’t.”

From the distribution of ENPs to navigation, propulsion, and even access to certain areas of the ship, Earth controlled Nautilus’sessential functions. The crew could follow directions and send messages back to Earth. That’s it. In the early days of space flight, scientists and pilots trained for many years before going into space. Once there, they performed the essential responsibilities. Not anymore. Space crews had been reduced to glorified cargo—kids taken from the encampments for noble goals and small compensation. Parents had been promised that their children would be trained and sent into space to save humanity. None of those taken were brave enough to ask if their parents had been told about the surgeries, and none of them wanted to know if their parents selflessly sacrificed them for the good of all or selfishly traded them for a bit of extra food. Faye knew that those answers didn’t matter because, like the kids, the parents never really had a choice.

###

Lying in her upper bunk that first night in the Institute, Faye had cried herself to sleep, oddly comforted by the gentle sobs which emanated from the bunks around her. The greasy saltiness of the cheeseburger a distant memory after a day spent being stripped, showered, shaved, poked and prodded—all while forced into silence by the adults processing them. She wondered if the doodlebug had felt this way this morning. Jerked from his home, no choice and no idea of what came next.

On the second day, their trainers divided them into groups and shuffled them into a small geodesic dome. When she entered, she immediately became dizzy and steadied herself with the frame of the door. The entire floor of the dome was covered in water. A small ledge, with just enough room for two people to stand on, was affixed at her feet. Others of her cohort already splashed in the clear water.

“Go on. Get in the water, Faye,” their handler told her. She wasn’t sure she could. Her feet were frozen in place. Thoughts of Tommy ran through her mind as she tried to tell herself that the other kids seemed fine so it must be safe. She felt the palm of a hand between her shoulder blades and then a split second of weightlessness before she crashed into the cold water. She surfaced, sputtered and wiped the water from her eyes. It had a crisp clean smell which tickled her nose. She raised her arms and looked at them fearfully, waiting for bubbles to appear under her skin. Nothing happened.

“What are you looking at your arms for?” the boy—she thought his name was Jake—standing next to her asked.

“I wasn’t sure the water was safe. It isn’t where I come from”

He nodded, “I’m just happy to see any water at all.” He turned and headed toward a group of boys splashing each other. She cupped some of the clear water in her palms and let it dribble out slowly.

They spent the next twelve hours in the water: exercising, eating, performing random and pointless tasks such as putting something together and then taking it apart, and stopping periodically for their handlers to take physical readings.

That night, Jake asked her about the water again, and she told him about Tommy and the river. She told him how she often wondered where the river went or even where it came from and that she and Tommy had daydreamed of building a raft and going exploring. Tommy always said, “We’ll be just like Huck and Jim.”

“I didn’t know what he meant by that,” Faye said “and now I don’t think I ever…”

“It’s an old book,” Jake interrupted, “my grandpa used to read it to me.” Jake spent the rest of the evening telling her everything he could remember about the story. He reminded Faye a lot of Tommy—happy, smart and never worried. Before the two men arrived, she would have done anything to get on a raft and leave. Now, she was less sure.

Over the following weeks, they spent days in different domes, each offered a different extreme climate—cold, hot, humid, dry, thin air, thick air, and air that reeked of sulfur and metal.

###

Soon after Faye and Jake learned that they had been put onto the Europa project, the operations started. Each one brought them physiologically a little closer to living in Europa. After the third, and so far, most painful surgery, Jake had reached across the small divide between their beds and took her hand, “Nothing to worry about, Huck. They are getting us ready for Europa. We are going to save humanity.”

“Well, either us or the Titan, Mars, Callisto, or Ganymede crews,” she replied sarcastically.

“Ok, fine. But, no matter what, it will be encampment kids. Who would’ve thought?” he turned away and stared up at the ceiling dreamily. “The fate of humanity in our hands.”

“Fins more like,” she chuckled as she ran her fingers along the webbing between his and wandered what it would be like to breathe water.

###

Faye gripped the handle near the porthole staring into Europa’s eye again for the tenth straight day. That morning the ration rack had descended but there were no ENPs to take. Most of the crew waited in the common room for the lunch rack, hoping that it had just been a malfunction. Faye suspected that the transportation module had run out of rations. Luckily for them, she thought wryly, going hungry was nothing encampment kids hadn’t endured. The crew should have transitioned from the travel to the descent modules of the Nautilus IV days ago. But the hatch between the sections remained closed and Earth remained silent. No doubt there were rations in the other module but no amount of prying, banging, or pleading convinced the hatch to open. By now, they should be exploring, setting up habitats, and establishing communication links. But, Europa, apparently, had other plans. She didn’t want them here, Faye thought.

She shivered. She had come to love the feeling of the water surrounding her skin but lately the water felt colder. She felt a slight pressure in the water on her back.

“I know you’re there, Jake, and I am not in the mood,” she said, without turning around.

“Please look at me, Faye,” he said. She slowly turned to face him.

“There’s nothing to worry about,” he said. “They’ll send us down soon. And, if they don’t, we’ll find a way into the descent module and head down ourselves.” The flaps of skin on the sides of his neck closed as he held his breath. He always did that when he lied as if he couldn’t breathe until the lie was accepted.

“Yeah, sure. Sounds like a plan,” she said, letting him breathe again. She turned back to the angry, unblinking, eye.

###

In a small, darkened office in Houston, an analyst looked at screens and screens of data sent from the Nautilus IV and its probes.

“Did we get the readings back from Europa?” a man with a receding gray hairline asked as he stepped into the analyst’s office.

“Yes, Mr. Lewis. It’s confirmed. Europa’s not viable for this crew. Ocean pressures are higher than expected in the anticipated temperature zone. We’re not sure why,” he replied.

Lewis just stared at him so he continued, “It could be faulty probes, maybe the pressure is cyclical or maybe changing currents or tectonic shifts have altered it,” he stammered. “Regardless, the crew has not been modified to survive these pressure and temperature combinations.” The analyst flicked his hand to display a chart on the center monitor.

“Well, that sets us back a bit,” Lewis sighed. “Maybe one of the other moons will pan out better,” he trailed off as he flicked his eyes to the crew roster displayed on an adjacent monitor. “You know, I remember buying one of that crew her first cheeseburger many years ago. Too bad,” he said as he sucked air through his teeth and stepped back into the hall.

“Wait. What should I tell the crew?” the analyst asked.

“Don’t tell them anything. We’ll adjust the pressure tolerance on the next batch and send them out. They can salvage the IV, the biomatter and the colony equipment. Onward and upward,” he said as he slapped the door frame twice on the way out. The analyst heard whistling as the man receded down the hall.