Pulp /’pəlp/ n.

1. A soft, moist, shapeless mass of matter.

2. A magazine or book containing lurid subject matter and being characteristically printed on rough, unfinished paper.

—American Heritage Dictionary New College Edition

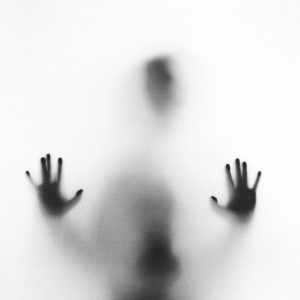

I can’t breathe. I can’t see. I can’t feel anything. I can’t fucking do shit. Am I still floating somewhere inside the cage? They’ll dock me sooner or later. My blood’s iron is filling my nose, lungs, throat, and eyes. Mountains of heat are swelling all over my face.

Fleeting shadows swirl in and out of the slants of my vision. Are they docking me? I can feel hands everywhere on me. I’m floating backwards. I try to lift my arms, but I can’t. I try to move any part of my body, but I can’t. I can only use my chip.

###

I gesture to Ali’s friend in the car next to us to see if he wants to smoke. The shouting will barely cut through the whine of our motorcycle and the eternal love Lebanese drivers have for their car horns. He looks at me, confused. He turns around to Ali in the driver’s seat, one hand on the steering wheel, eyes swaying between the road and us, and talks to him, trying to glean what I want. They exchange a few words, after which the friend turns toward our motorcycle and makes a cutting gesture across his throat with his fingers, his lips mouthing, “I don’t smoke,” as Ali draws a smile behind him.

Everyone smokes hashish in Beirut; he’s just new.

I wait a second until Ali’s eyes meet mine again and gesture to him that I’ll hit him up in about an hour. He nods, and we go our separate ways. Mohammad tilts his head toward me. I lean forward so I can catch what he’s going to say before it gets carried away by the wind his motorcycle is splitting through.

“How many drops do we still have?”

“Two,” I shout in his ear through the high-pitched whine of his Yamaha Aprio.

“Where to now?”

“Chmaitelly Chicken.”

He cranks the Aprio, and it cries like a wild dog.

We wait at the Bechara El Khoury intersection. I get off the bike to rest my ass a bit and keep a lookout. Mohammad’s eyes glow white, signaling that he is using his chip, probably scrolling through TikTok. On the opposite side of our spot, to the right, is the chicken shop. A hologram of a cartoonish chicken marches up and down the top of the entrance, carrying a white flag with the name of the place— not only the shop’s but also the intersection’s famous mascot. To the left stands the ominous statue of the first Lebanese president, after whom this intersection was named. I remember my grandfather telling me how his presidency ended after people started protesting his decisions and making accusations of corruption.

“So you can see what this country was built on and by whom,” he said.

“Did you know Bechara El Khoury was forced to resign because of corruption?” I tell Mohammad.

“No shit?” he answers, laughing. His eyes cease to glow as he turns toward me. “Figures. Wouldn’t expect any less. The history teacher practically rode his and Riad Al Solh’s dicks off talking about how they gave Lebanon independence.”

“Yeah, they never tell us what happened afterward, do they?”

“How do you know?”

“Grandad hated both their guts. Something about killing Antoun Saadeh.”

“Who the fuck is that?”

“Beats me.”

I see a Suzuki Address 125 stopping in front of the chicken shop and then just… stops. The driver sits on his motorcycle in front of Chmaitelly and doesn’t budge for a solid three minutes.

“I think our friend is here,” I tell Mohammad.

I hop back on, and we cross toward him. Mohammad parks right behind him, and the smell of rotisserie chicken hits my nose like a hard slap.

“Bilal?” I ask, seeing if that gets a reaction.

He turns his head toward me. He is a new customer, but it doesn’t seem like this is his first time buying.

“Yeah,” he mouths with a slight smile and a nod.

“Follow us.”

We slowly start heading towards the Khandak region, and Bilal follows.

Mohammad makes sure to drive on the right side and keeps a little bit of distance in between to force the client to switch the money from his left hand to his right. I pull out the Aluminum foil, tightly wrapping the big stone from my cargo pants’ lower right pocket, and switch it to my left hand.

As we start extending our arms for the transaction, he drops the money and tries to grab me. Mohammad spots what’s going on and cranks the Aprio. We have a split-second head start since the fed’s arm was forced off the throttle to give us the money. Mohammad turns on the Akiras through a hidden, custom-placed button next to the Aprio’s horn. They’re not street legal, but that never stopped half of Lebanon’s bikers from installing them; you just need to get around the Internal Security Force’s spot checks.

A trail of red light starts spewing from the microscopic pores drilled through the taillight’s cover. The light motes begin drawing two lines that explode in spherical patterns every half meter, blinding the fed. I look back, and I can only see the silent, spiky explosions of the Akiras, like bright, holographic sea urchins. I pull out my old BHP pistol just in case.

The motorcycle suddenly swerves, and when I look forward, I see a white Chevrolet EV trying to cut us off. Mohammad knew what he was doing. He took a hard right into a tight road leading into the maze that is Khandak. I shoot to keep them ducked until the hard wall of a decrepit building blocks my view. My ears are ringing like crazy. Mohammad takes another turn. The blood rushes through my veins so fast that my limbs start to shake.

###

I am floating underwater. The oxygen mask is messing with my flow. Every time I move, its gray hose gets dragged along, and it sometimes gets in my way as I throw a punch. It coils at the bottom on the blue tiles, then goes up near the edge, connecting to the oxygen tanks placed on the side of the training pool.

The water makes moving and maneuvering much more difficult—a good substitute if you don’t have enough money to register at a gym with actual anti-gravity cages. Joseph, the coach, has propellants installed in his arms and is using them to throw punches faster than I can block.

I hear their minuscule roars, tiny rockets screaming out from his elbows, bellowing pillars of bubbles towards the top as his dense right knuckles close in on my face like a torpedo. I strain my muscles to block as quickly as I can, but the left knuckles are already hitting my cheekbones, throwing my head to the opposite side, soon followed by the rest of my body. I’m upside down, needing to reorient, but Joseph is already coming at me with a kick. I manage to grab his leg and use his momentum to adjust my position while pulling him down. Now, the roles are reversed. I give him a quick titanium-meshed knee to the forehead. He tries to take advantage of the momentum gained from my hit to deliver a left kick to my face, but I’m quick to block. However, I suddenly feel like I’m going to spill my guts inside the oxygen mask. I scurry to the edge, get out, lie down next to the water, and pull the mask off between fits of coughing.

“The fuck just happened?” I manage to spit out.

“I used the finger thrusters to power an elbow to your stomach,” he replies as he removes his mask and climbs out of the pool. “You know what my upgrades are; you should have planned accordingly. Predicting one hit ahead will get you nowhere.”

I take in a deep breath. I cover my face with both hands. He is right.

“You’re still too slow.” He kneels next to my head. “Ziad will have better implants than the ones I have now. You need to either get better or get beaten to death. Choose one.”

I nod, stifling the rest of the coughs.

“Shut it down,” he says, getting up and heading toward the showers.

The assistants close the oxygen tanks, then the underwater lights. I get up and walk toward the check-up machine in the corner. I slide the transparent door open and stand motionless in the middle. The entire thing looks and feels like a state-of-the-art shower booth. Exactly three seconds later, the screen in front of me lights up with an abstract image of a male human body. It highlights the locations of my injuries, names them one by one, and provides the approximate age and recovery time for each. The new injuries are minor lacerations on my face, microfractures in both cheekbones, and strained stomach muscles. I go to cool off on a bench before taking a shower. After a while, I feel a body sitting next to me. It’s Ali.

“Still want to do the match?”

He thinks it’s a bad idea. I can hear it in his tone.

“I still have time to train.”

“No money to buy any upgrades, though.”

“I don’t need them.”

He lets out a small chuckle.

“We both know you do. It’s just a money grab for him. It’s life and death for you. Is it really worth it? What are you getting out of this?”

###

My two cousins place me against a wall on the roof of our house and prepare to execute me. My small child’s hands are powerless against their bigger, stronger bodies and presence. I stand there, silent as a lamb. They load the BB into the air rifle and aim at my legs—my mom told us to never aim it at the face. They try to look like experts as they align the muzzle with the thin twigs I stand on. The first two miss completely. The third grazes my left leg. I feel excited, and my heart pumps faster and faster. The fourth connects with the front of my lower right leg.

I cry more than I should. It doesn’t really hurt that bad; it was just a fleeting sting. They come to me to try and quiet me down as they stifle their laughs, still carrying the exhilaration of hitting the mark like trained assassins.

My mom comes up the stairs with my uncle and starts scolding them when she sees the air rifle and my hands grasping my leg. My uncle quietly looks at the scene with a smile on his lips.

She checks it; barely anything is there. She takes me down, and my uncle follows suit after taking the rifle from the wannabe killers.

Later that evening, I catch him outside, smoking alone, the smell hanging around him as always. He tells me about my great-uncle, who injured his leg in that very same place when he was fighting in the South back in ’24. It’s the first time I’ve heard about this. I ask him more questions, but my uncle says it doesn’t matter anymore; it’s history.

“Not that I would know much either. He went back to the front shortly afterward and never came back, and your grandfather didn’t like talking about it much.”

“Why not?” I ask him.

“He didn’t like that path. Our family always carried guns and fought, as far back as I know—your great-great-granddad, his son, some of his sons, even me for a while. Dad, for some reason, was immune to that. He didn’t like it. I got into many fights with him. One time, I ran away from home to do standard training with you-know-who. He went to their headquarters and refused to leave unless they brought me back, and they did.”

“Who’s ‘you-know-who’?” I naively ask.

He points with his thumb towards the back of his head, where his chip is installed, and says, “We can’t say everything when we have guests now, can we? Anyway, you’d better not disappoint your grandad like me and your father, got it?”

I am not satisfied with the answer, but it seems like I have to settle for it.

“Got it,” I answer.

“Good. Now, let’s go back inside. It’s getting chilly out here.”

I follow him back into the apartment, and as we sit in the living room, I can’t help but stare at a picture hanging on one of the walls of my grandpa. On his lap, a child who was going to die at the age of thirty-two, fighting on the coast of Tripoli. In his hands, a baby—my uncle. Proudly next to them stands a man in his 60s. He had male pattern baldness and a neat, white mustache. He looked rough; I could almost hear his voice, like bark scraping against concrete—my great-granddad.

###

I can hear the whizz of the sniper’s bullet as it zips across the ditch’s edge. I try to crumble my body and sink it down in the mud as deep as it can go to avoid the shots, becoming soaking wet from the small stream running through it. He’s nestled in the church’s bell tower, waiting for an idiot to try and cross his corridor. I am that idiot.

He toys with me, firing one bullet to my left, then one to my right—alternating, like a cat taunting a mouse. He knows I can’t go anywhere. He knows where I am heading. I call for Marcel to cover me.

Marcel is a beast of a man. We joined the Syrian Social Nationalist Party together back in ’75. He comes out of the building carrying an old PKM, ready for action. Despite having a well-eroded barrel and a worn-out trigger spring, he loves using it every chance he gets, lighting up like a kid on Christmas morning.

As soon as he starts delivering suppressing fire, I jolt out of the ditch and run behind the nearest building on the left. It’s smooth sailing from here; I know Moallaka like the back of my hand—it’s where I grew up. I slip into the small alley next to the building, two buildings up, one right, and now the only thing separating me from the entrance of our makeshift base is a concrete block wall. The loud bangs of the PKM stop, replaced by faint, softer pops coming from the other side. I feel a presence above and look up to see Assaad watching me from the second story of the building, his AK drawn—expecting me, but still cautious. I jump over the wall and land right in front of Marcel.

“Thanks, Marcel. If it wasn’t for you, I’d be done for,” I tell him, still trying to catch my breath.

“Don’t get too happy yet. The sniper didn’t get you, but Assaad sure will,” he replies with his signature deep voice, traces of a happy child still radiating from his face.

He puts his hand behind my back and pushes me inside. Not even one step in, and I can already hear Assaad’s commanding voice filling the entire room.

“What the fuck were you doing out there?” he greets me.

I pull out a cluster of white grapes from my right cargo pocket, and everyone’s eyes widen.

“They’re all washed too,” I say with a big smile.

“You little weasel,” Marcel’s voice rings from behind me, and I see his hand reaching in to cut a pedicel off. I start distributing the other pedicels to my comrades until I’m left with one. I start picking the grapes off one by one; the sweet water inside feels like life.

“My uncle’s vines are just on the other side, so I thought I could get a few,” I said to Assaad, with the grape’s juices dripping from my lips, as if this would absolve me of my stupidity.

“Hussein, you’re either a dumbass or an imbecile—no third option,” was his judgment as he placed a grape in his mouth.

“There’s a ceasefire; he’s the asshole who isn’t abiding by it.”

“You shouldn’t have even been there!” He raised his voice a bit, but it’s always impossible to tell whether he’s genuinely angry or just teasing you. “Just go inside; I don’t want to see your face. I’ll take care of this,” He says, raising a walkie-talkie twice the size of his hands and preparing to speak into it.

I go into the living room, now a makeshift bedroom with the sofas converted into beds and sleeping bags scattered all over the floor. Marcel is cleaning his BHP pistol, a prize he took from the cold hands of a Lebanese Forces fighter.

“Thanks for the grapes, champ,” he says, throwing a brief glance at me before going back to what he’s doing.

“No problem. Would have been a waste to just leave them there,” I say as I sit down on my soft bedroll next to him.

He has a small notebook on his leg with a list in it. I can’t understand a word of his handwriting, but I think one item is rubber bands.

“What’s that?” I ask him.

“Just some stuff to bring with me the next time around.”

“Thinking about the next time already?”

“There’s always a next time until there isn’t.”

“I’m thinking of making this my last. I’m settling down.”

“So soon?”

“Yeah, I promised my mother grandsons. She wants a Abbas to carry my father’s name.”

“Yeah, my dad wants a Ziad, and Ziad will get me a Marcel, and Marcel will get him a Ziad, and Ziad will get Marcel a Marcel.”

“It’s a Abbas and Hussein cycle for us,” I tell him in between laughs.

“I’m not that pressed about it, though. It’ll have to wait for now. There are more important things at hand.”

“More important than starting a family?”

He looks at me, almost in disbelief, for a moment, then goes back to his hobby.

“My father did the same thing, you know. He used to fight with the communists back in ’58, and then he just stopped once he met my mother.”

“The communists? Hah! Our fathers were probably on opposite sides of the same front back then. I joined here following in his footsteps.”

“Yeah, I figured. He never really liked me joining the Nationalists, but who cares? Now we’re all fighting on the same side.”

“How the tables turn, am I right?”

He puts the pistol back together, its surface now slick and shining. I can see the reflection of my eyes on the slide, growing more tired as the adrenaline continues to drain.

###

I look in my rearview mirror and see that my eyes are practically black holes. Ever since we had to evacuate our apartment, I haven’t been able to sleep right. Even though my in-laws’ house is in a “safe zone,” I could still hear the bombs every single night, wondering if it was going to be my building next, wondering if I would ever get to see it again.

My son finds ample entertainment in the scenes of destruction and isn’t as fussy as he usually is on long drives. He’s sitting behind me, absolutely hypnotized by what the neighborhood has become. The view of rubble fascinates him. He asks for my attention and points out the metal rods, twisting and sticking out of a flattened building like the legs of a dead spider. He keeps telling me and Mariam about the things he’s found in the rubble: toys, CDs, posters, furniture.

Traffic in Dahiyeh is suffocating, and the smell of leftover war doesn’t help. I’ve been trying to cross Sayid Hadi Highway for the past hour and have barely moved past two of its endless intersections. I find myself following Hussein’s lead, exploring the crumbled buildings from the car window.

It feels surreal. I look around for a while, and at first, it feels like a normal neighborhood. Then, out of nowhere, between two standing buildings, I find rubble and the balconies of the top two stories of a previously ten-story building at ground level. Sometimes, the bombed structure sweeps parts of the surrounding walls, revealing someone’s bedroom through the collapsed section. Mariam is quiet the entire time, still unable to believe her eyes.

I hear loud banging coming from the back and a man shouting as if a life-or-death situation is taking place. Two men on a motorcycle, long black beards, hoodies. The driver is hitting the back of my car with an open palm.

“Move, you fucking moron! Move it!”

I can’t move anywhere; the front of my car is almost kissing the Chevrolet Malibu in front of me. I can’t really say anything—he probably has a gun. There are no macho men when guns are involved; it’s a cheap death, and the tolls from road rage incidents show it. Mariam starts looking back, then at me, then at Hussein, and then back at me.

“Can’t you go a bit further? Let him through, he’s going to kill us,” she says, almost crying.

“I can’t go anywhere, Mariam. What am I supposed to do, lift the car?”

I look in the rearview mirror. Hussein is just sitting there, not knowing what to do.

I start feeling hot. The temperature is high for a November day, and I’m dressed in black. I just came back from my uncle’s funeral; he was martyred in the south, and there’s still no news of my brother. The asshole bangs on my car again.

“Fucking move it motherfucker! What is wrong with you?”

Hussein is starting to get scared. Mariam is on her phone, texting someone furiously.

“What’s wrong with this guy?” he innocently asks.

“Nothing, never mind him,” I try to keep him calm. I stick my head out the window and look back at the men on the motorcycle. “I can’t go anywhere, I’m stuck. I can’t do anything.”

He mumbles to himself and starts looking around for other openings his motorcycle can fit through so he can go on his way.

After a long minute, the Chevrolet finally moves, and I’m able to move forward a little to let the motorcycle through. The gas pedal feels like a ton. He passes and stops next to my window, staring me down. I don’t look at him. He hits the throttle and disappears between the vehicles. I can’t believe my uncle died fighting for this. And now I have to go back to half an apartment— the other half is either vaporized or on someone else’s balcony, roof, backyard, or whatever. I need to get out of here. I look at Mariam. She is staring at the spot where that motorcycle last was, poison dripping from her eyes.

It was already difficult before the war to find a place to rent; now it’s nearly impossible. Nobody wants a Shia tenant anymore. The “safe” Christian areas were already iffy about renting to people who weren’t Christians. The Sunni areas aren’t much more welcoming when tensions are high. And now, after the ceasefire, every area that doesn’t have a Shia majority will mark you as persona non grata once they know your sect. I look at Hussein again. He seems a little shaken.

“What do you think about converting to Christianity and just leaving this place?” I ask him jokingly.

He giggles at the silly idea.

###

“Congrats, big guy,” Ali tells me as we start digging into our burgers. I finally have enough money to install some fortification in my skull. Can’t spend resources on offense, might as well try to build a better defense.

“So what are you gonna do?” Mohammad asks.

“I’m thinking about reinforcing my temples and chin with graphene. It’s relatively cheap and quick. The fight is in three weeks; I can start the operation on Thursday and register it with the association on Monday.”

“Hey, you’re the one fighting Ziad, no?” I hear someone say from my left.

“Yeah, you got it,” I answer.

He smiles wide.

“Good luck on that fight, it’s going to be tough. I hear he installed some new mods, so the prize for beating him went even higher.”

“Good, so I’m getting two new motorcycles next month.”

A short laugh fills both tables.

“Sure hope so, man. The entirety of Dahiyeh is cheering for you. Good luck,” he says as he and his two friends get up to leave, leaving a mess of crumpled paper and cartons behind on the table.

“So what’s the plan after this?” Ali asks.

“There are a few drops me and Mohammad gotta do. We’ll be done at around nine. After that, I was thinking we could go to Mar Mkhayel and get some drinks. You up for that?”

“Yeah, sure thing. Let me know when you’re done. I need to take care of a few things first,” he says as he gets up to leave.

We finish up and wash. Mohammad and I study the logistics of our drops. After it’s all settled, we head out, and suddenly my head is ringing, and I’m on the floor. Heat is making its way from inside my skin toward my right temple. I look up, and it’s the guy who was at the table next to us, along with more of his friends. He’s covering his face with a rag, but the dumbass is still wearing the same clothes.

There’s a flurry of kicks, metal bars, and aluminum bats showering me and Mohammad as we scramble on the floor, trying to kick at random. Then, black.

I wake up with both the money and drugs gone.

###

Mohammad is dead. His mother refused to let me attend the funeral. She said I was a bad influence.

My heart is racing. My face is still bruised from the beating I took. It doesn’t matter. I either get the money to pay back for the stolen stuff, or I’m done for. Honestly, either outcome is fine by me. It’s not worth coming out of the cage alive if I don’t win.

I get a final physical check before I go out. They ask me one last time if I still want to go through with it, despite everything. I nod. Only an idiot would step into a fight like this. I am that idiot.

The door opens, and light floods in, blinding me for a second. The cage is there, a ring girl swimming in its heavy air.

The shouting is deafening. Amid the chaos of faces, I spot my mother’s, somewhere in the middle rows. My name floats above the cage as I enter, and she winces at the scene. The cage announcer bellows the name into his mic. The spectators’ roars crash against every corner of the venue like waves.

I bathe in the moment. The entirety of Dahiyeh is cheering for me, and for a brief moment, everyone is carrying my name.