“There is an animal,” I tell my young apprentice, “that can make other species protect it to the death.”

Clay keeps notes as we crouch low in the dugout, watching the ant-wasp hill under the soft redlight of the third of our thirteen suns. Strange—the words Mission Log had been printed on the top of each page, which I struck through and replaced with Natural Observation Journal at the beginning of our apprenticeship.

“Why does it do that, Scholar Jordan?” Clay asks, looking up from their slanted script with a smudge of ink on each cheek.

I forgive my apprentice for their impatience, and for taking their eyes off the wonder unfolding before us. They are young and require guidance, which I have to give in abundance. Clay must learn how to infer answers through observation, the way I did, watching the animals and plants in their redglimmer habitat, they so graciously share with us.

“Why did you become a historian’s apprentice, Clay?” I ask instead of answering their question, wanting to remind Clay of their calling.

Clay considers this, shifting in the dugout. The ant-wasp mound—the object of today’s observation—remains still and silent. “I couldn’t apprentice to the baker because of my allergy to carob-thyme flour in its raw form. Nor to the masons of our village, for I don’t have the musculature necessary for stripping metal from the sleeping giants to repurpose into shelter. Nor do I have a soothing voice to sing the giants to sleep like our priests do at the dawn of each of our thirteen suns. But my penmanship and observation skills are good, Scholar Jordan. Even when I make mistakes.”

I made mistakes once, too, when I was the first historian, nobody else to teach me what to look out for, how to be gentle with the world so it would be gentle with me in turn. I ate a plant the tiger-monkeys avoided, and it stripped the microbiota from my guts, almost sending me to death’s doors. I didn’t know to take shelter from the rain like the deer-wolves did, so it bore acid circles into my skin. I even got bitten by the ant-wasps once, and my skin fevered like I’d swallowed the suns, and a headache split my skull for days.

This is what I always tell Clay: There’s so much to learn from one another.

My apprentice turns their eyes toward the mound. Their half-lidded look of boredom shifts into excitement as the skunk-fox—majestic red as all the animals, as the thirteen suns, as the air we blessedly push in and out of our lungs—approaches on stealthy paws.

The fox noses around the powdery hill where the ant-wasps live. It has a long muzzle and longer tongue, which the fox shoves into the hill’s opening. Just as quick, the fox rears back.

“The fox got bitten,” Clay murmurs, taking frantic notes, feverish with knowledge. But they must learn, too, that knowledge is a gift our red earth and its redder animals give us, not one we take lightly. “The ant-wasps… released their toxins into its bloodstream?”

The fox stumbles about, confused, whining in pain. Then: it settles, a beatific calm spreading across its face. The other skunk-foxes of the pack howl a question from their nearby burrow.

I wince in learned commiseration, knowing to feel compassion for all living creatures, for they are not to blame for their nature.

“There is an animal,” I tell Clay, “that is small and defenseless, and there for the taking. So it needs a different mechanism to prevent invading species from harming this animal and its home.”

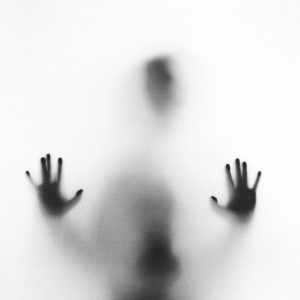

Toxin-drunk, the fox positions itself over the ant-nest, facing its brethren as the pack approaches in howling hunger, teeth bared and snarling. By all rights, the fox should have joined its people, helped them root the ants out, and crunch them between their jagged-toothed jaws. But we watch as the fox’s invaded brain instructs it to act as the ants’ protector instead. To claw and bite the other foxes, not recognizing them as its own. The other skunk-foxes have no choice but to fight back. The foxes end up dead, all of them, having torn each other to pieces.

To its last breath, the toxin-drunk fox dies loving the ants it was compelled into protecting.

Clay writes this in his notebook and, oh—perhaps there is a bit of a poet in the youth. A good trait to have as a historian.

“May you return to the red soil and redder sky, and come back as the ant-wasp in the next cycle,” we breathe a farewell prayer toward the fox’s remains.

“You’ve done well,” I say afterward, clapping Clay on the back as we dust off.

Together, we set off back toward our village through the diffuse redlight, over the crystal-hardened ground that shields the soil from the elements like an exoskeleton. It is time to take the observations of the ant-wasps and the skunk-fox to our people, share a meal around the fire made warmer still by the stories we tell.

###

The giant beasts surround our village in a somnolent circle. Numbers have been embossed into their metal hulls that no natural historian has so far managed to decode. The beasts have dug their metal mandibles into the ground, broken the crystalline crust to upturn the red soil underneath. What waste, what violence. Thank the thirteen suns our priests learned the songs to keep the beasts dormant while we strip them clean of their components. The metal giants are unnatural, and I only choose to focus on the natural world. I hope my apprentice, though young, follows in my footsteps.

We aren’t even past the ring of sleeping beasts when our people intercept us.

“Scholar Jordan!” the head-priest calls, her eyes luminous with fear. “There’s something you need to hear.”

A sleek, compact box has been uncovered by a village child playing near the giants. It was buried in the soil under the sharp tip of a half-submerged beast, as if someone had tucked it there, where it wouldn’t be easily found.

I hold it between my palms with some trepidation and press the largest button:

Sergeant Jordan, report immediately. I repeat. Sergeant Jordan—

I almost drop the god-voice box. Why does it know my name and speak it with such concern, such familiarity? Does it want to inject confusion into me, the historian tasked with making sense of the marvels and the dangers of our natural world?

The priests clamor to apologize. Scholar Jordan, they say, we must have not prayed hard enough to keep the giant beasts sleeping. Forgive us, Scholar.

Clay, too, turns wide eyes on me. They were so impatient before, but now my apprentice is a child needing to be told that the world they know won’t collapse before their eyes.

The messages from beyond keep playing, each one splitting my temples with a red-sun-fiery sort of pain.

We know the terraforming equipment has been compromised. We’re losing more and more signals. But I really hope you and the crew are alive, Jordan, even if the machines have malfunctioned.

So the trickster-voices trying to confuse me belong to the ones who sent the metal beasts here to wound the ground before our priests sang them to sleep. The metal giants are wrongness personified, their bodies glinting perversely against the redlight. The disembodied gods planted these excrescences, like prophesies warning of an incoming invasion.

The final message is this, and it makes my people blanch all around me. They huddle closer, an animal pack.

Jordan, we know the mission has failed. I’m authorizing a rescue vessel to be sent your way. We’re bringing you back to the base. Whatever happened to you, just hold tight, and we’ll figure it out.

Stories always end up making sense, I often tell Clay. There was a reason we chose to observe the ant-wasps when we did, a lesson to help our people with our defense against these tricksters.

Sergeant Jordan… Scholar Jordan… so which one is it? My head pounds and my body burns a febrile red. But I think of what I’ve learned through my natural observations, and I drive the doubts away, the fever clearing from my mind.

“We need to strip the giants for weapons,” I call out to my people. “Anything heavy and sharp will do.”

We need to protect ourselves from the gods in the voice box, coming at last to claim our home for themselves. And I? I need to take the lead. For my people, and Clay, and the ant and fox and red, red soil.

A parable: as the ant-wasps work together to defeat the skunk-fox’s wiles, so will we work as one to defend our planet tooth and nail against these strange intelligences approaching from beyond.

Yet I look at Clay, who clutches their observation journal to their chest, and I can’t help feeling like perhaps I’ve taught my apprentice the wrong lesson.