GERMINATION

The first bud sprouts from Charlie’s left thumb.

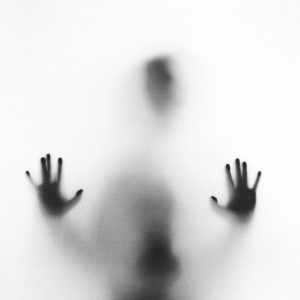

You think you’re dreaming. Another nightmare, but so much more fantastical than the ones you usually have. Charlie crashing his plane in the jungle. Charlie’s parachute failing. Charlie screaming as napalm melts flesh off bone. Charlie, reporting for duty one leg short, clumsily hefting a gun in a two-fingered hand. He’s been back now for two months and a day. Been off the battlefield for two months longer than that. But you dream like he’s still gone.

Now, though, you’re both wide awake. Charlie shakes his hand vigorously. The bud wobbles but holds fast.

“For fuck’s sake, get me the nail trimmers,” he snaps.

He snips the strange appendage off at its base. No blood. No pus. Just an odd little thing, small as a pea and just as green. You have a strong desire to roll it around between your fingers, to press crescents in it with your nails. But Charlie is already wheeling his way towards the bathroom, and he flushes it down the toilet without a word.

You ask if you should call Dr. Hines.

“All I do is go to the fucking doctor,” says Charlie, and turns on the television, drowning you out with the sound of the morning news: all war, all the time.

You want to ask how he can stand it, to watch people just like him pilot planes just like he did, misting forests with chemicals he calls Rainbow Agents. You want to point out the irony of it all: labeling some instrument of war with the ubiquitous symbol of hope and peace. Instead, you set a freshly brewed cup of coffee in front of him (scalding, bitter, and black), slather strawberry jam on his toast, and switch the channel from war to Bugs Bunny. Charlie doesn’t argue. He doesn’t smile, either.

GROWTH

Back when he was fit and able and free, Charlie spent his days doing things. He’d work. Mow the lawn. Fish with his friends. Go to happy hour. Now the chair keeps him from bricklaying, and you can’t afford a ride-on mower. The fish are still there, but his friends aren’t, all gone to war just like him, some who might yet come back and some who never will. Charlie drinks without an audience, trading beer for whiskey, stripping away everything that makes drinking fun.

He’s not exaggerating when he says that all he does is go to the doctor, and you’re thankful you don’t need to nag him. He hopes that when he rolls into the hospital, they’ll tell him they’ve found a new way to regenerate limbs, to piece him back together like Humpty Dumpty. They’re making new advancements every day, he tells you drunkenly one night in a surprisingly touching moment of childlike hope. You don’t have the heart to tell him he’s wrong. Soon, he’ll be fitted with a prosthetic. You’re counting down the days, thinking you’ll make him a cake. Get some balloons. Celebrate.

But more strange growths emerge in the places where three of his fingers used to be, spreading up his left arm. He prunes them the moment he notices them, leaving behind small, razor-thin incisions.

Dr. Hines asks to speak to you in private when Charlie’s wheeled off to physical therapy. He sits you down and asks if Charlie self-harms.

You shake your head. Hesitate. Then: “He gets these growths.”

“Like warts?”

“No, like…” you trail off. How do you even explain what it is you see each morning? “…Seedlings.”

The doctor blinks several times. His eyes are huge behind his glasses. “What?”

“Seedlings. Think acne, but … botanical?” It sounds even stupider than it did in your head. “Have you ever seen anything like that?”

From the look on his face, he hasn’t. He seems to be deciding whether he should commit you or laugh. You laugh first. He doesn’t know you well enough to detect it’s forced.

“Just kidding,” you say. “It’s probably warts.”

“I’ll prescribe him something,” Dr. Hines says. “Don’t let him cut them off again. It’s bad for you. Could lead to an infection.”

In the car, Charlie turns on you with an ugly glare. “You shouldn’t have said anything.”

“I’m sorry,” you say. “I’m just worried. It’s weird. And getting worse.”

A gaggle of tie-dyed protestors chant, Hell no, we won’t go! outside City Hall. Charlie rolls down his window and lobs a half-drunk cup of coffee into the crowd.

“Fucking Commies,” he yells with such rage you think he might burst into hellfire. You speed away as the light turns green. Your hands shake.

In the driveway, you help him into his chair. “They just don’t want more people hurt,” you say tentatively. “They want peace. Don’t you?”

“They’ll get peace when we win,” Charlie spits, and along the suture scars of his missing fingers, a network of little green tendrils sprouts, spreading slowly and steadily up his forearm. He stares, breathing heavily.

“We have to win,” he says, because how else can he justify what he’s done, what’s been done to him if they don’t?

He doesn’t talk to you the rest of the evening. He turns on the TV, obsessively watching the news. You make meatloaf (his favorite) and sneak some cauliflower in his mashed potatoes like he’s a picky child. That nigh,t when he thinks you’re asleep, you hear him cutting away the vines, weeping into an empty cup of liquor.

ANTHESIS

The tendrils creep along his body like the ivy on the side of the house, sprouting leaves and buds as they go. It’s like you’re watching a time-lapse nature documentary. He skips his next two appointments because he doesn’t want Dr. Hines to know, even though you don’t see any other way to fix this, if there is a way at all.

You don’t tell your friends. You don’t invite them over, either, but one Sunday you go out to breakfast. Sally’s a gardener. She loves plants. Maybe she’ll know, you think, but when she asks after Charlie, you lose your nerve and just say, “He’s okay.”

“Still treating you like shit?”

“He’s just recovering. It’s been very traumatic.”

“So nothing’s changed from before,” Sally says. “I don’t know what you see in the guy.”

“He’s very nice. Generous. Caring,” you say, though you can’t remember a time lately when that’s been true. You can’t really remember a time before that, either. “It’s not like he’s violent.”

“You don’t have to be violent to be a jerk,” Sally says under her breath. You know she’d suggest divorce if he weren’t crippled. But you swore to take care of him, and you will. Through sickness and in health. Even if that means doing a little pruning.

When you get back to the house, you feel instantly suffocated.

“Sally?” Charlie says when you tell him where you’ve been. “That woman’s a damn nuisance. She’s gonna fill your head with nonsense.”

“It might do you some good to see people, too,” you try, ignoring the barb. “There are support groups for veterans. Dr. Hines told me about them. Maybe you’re not the only one with this…” Illness? Problem? Infestation? “…condition.”

His nostrils flare. A vein pops in his forehead. You don’t know which part he’s furious about. And then, as if on cue, one of the buds blooms.

First one. Then two. Big scarlet flowers the size of your palm rapidly unfurl until his left half is entirely covered. You yearn to touch one to see if it’s as soft as you want it to be. He stares in disgust.

He tears off a flower, pinching it at its base, and tosses it on the floor, crushing it beneath his good foot. He rips them all off despite the pain, and you can only stand there and watch him destroy these beautiful, strange things that have somehow become part of him.

When he’s done, the floor is littered with them. His arm looks like he’s been picking at zits.

“Did it hurt?” is all you can think to say.

“I need a drink,” he says, and wheels over the already ruined poppies to break open a bottle of Jim Beam. You take your time sweeping them up. A few are still intact. You pick one up, the thin petal velvety smooth between your thumb and forefinger. It feels just like a normal flower. It doesn’t feel like it came from Charlie. How strange, you think, that in the few years you’ve been married, this is the first bouquet he’s ever given you.

The flowers keep blooming. It doesn’t matter that he plucks them. You hide matches and lighters so he doesn’t burn them away. You force him outside to get some sunlight, and to your surprise, he doesn’t complain. Instead, he leans backwards, closing his eyes. The poppies arch towards the sun.

“Maybe it’s the first step,” he says.

“Of what?”

“Growing it back. It could be a breakthrough. I could be a medical miracle.”

He sounds happier than he has in months. Maybe it’s the sun’s doing. Maybe he’s photosynthesizing. When he smiles, you feel your heart constrict. You’ve nearly forgotten what it looks like. You mourn that loss as much as he mourns his missing appendages. You wonder: if he got them back, would he really be whole?

DEHISCENCE

You don’t know why Charlie’s a garden. You also don’t know why it’s a garden of poppies. It could be anything. Sunflowers. Daisies. Cucumbers. But for some reason, it’s always poppies. You’ve become accustomed to waking up covered in red petals. Charlie struggles to get dressed; his pants don’t fit over the blooms anymore.

He won’t go out in public, and you can’t really blame him. He looks like a parade float. You pet the petals when he sleeps, because he won’t let you otherwise. It’s been like that since he got back. He doesn’t believe you when you insist the amputation doesn’t bother you. He certainly won’t believe you now that he’s a flowerbed.

When the first story breaks about Agent Orange, you both pause, transfixed. Birth defects. Malformations. Skin disorders. Cancer.

“Maybe that’s why,” you say when you’re able to speak past the lump in your throat. “You were near those chemicals all the time.”

“I sprayed them. No one sprayed me. And I wasn’t dumb enough to spill any.”

“Still.”

“They’re defoliants,” Charlie says. “They kill plants. They don’t grow them.”

“What if it’s karma?” It’s the wrong thing to say; you know it the second the words leave your mouth. It’s not his fault, you want to clarify — he just did what he was told.

He slams his bad fist down on the table. His glass shatters and slices through his palm, orange juice pouring onto the floor. He takes a deep breath, ready to shout his throat raw, then stops, and together, in silence, you watch crimson petals float to the floor instead of blood.

He swivels his chair around, his hand reaching for something, anything, and lands upon a vegetable peeler. He slices his thumb on the blade. More petals.

“Charlie—”

He presses the point into his wrist. He grunts in pain as he digs deeper, deeper as if his arm is soil and not skin, and when you finally wrestle the blade away and throw it across the room, you stare down at the mess he’s made. Petals flow out of the wound, tickling your fingertips, and when you look at the mangled flesh, you see a network of thin white roots instead of veins.

He laughs unpleasantly, hysterically. “Maybe it is revenge,” he says between wheezes. “God, wouldn’t that be funny, to be killed by a fucking plant.”

You don’t think it’s funny at all. The petals have overflowed onto the floor. The world’s a blurry sea of red.

“Stop crying,” he says. “Sew me up.”

He won’t let you call an ambulance. He makes you take your own thread, your own needle, and heat it on the stove, pulling stitches through his skin like he’s a quilt. He drains a bottle of whiskey to numb the pain.

“Least we could do is make opium out of the things,” he murmurs, drunk and delirious. “Sell it. Get rich. Get high. Could be millionaires.”

He falls asleep in the recliner. You throw up for thirty minutes, then sweep up what feels like a thousand petals. You dream you run an opium den, where Charlie smokes and smokes and never wakes up. But in the morning, you find him already making breakfast and humming a tone-deaf tune, cheerful as can be. Withered petals litter the clean floor. Nearly half the poppies are gone. The rest wilt.

“What did you do?” You ask, stooping to pick one up. It crumbles.

“Nothing. Just woke up like this.” He grins. It’s a grin you used to know, the kind that belonged to a kid boasting about his pilot license, wearing a bomber jacket, arm slung around your shoulders. It’s the grin you missed. Your heart skips. “Maybe I just needed to get it out of my system. Whatever it was.”

You start to make coffee before you realize he’s already done it.

“I’m sorry. Really,” he says. “I know what you’ve done for me.”

Give up your job, your hobbies, your friends. Sweep petals. Drive him to appointments. Make excuses about appointments. Sew up wounds like a barbaric nurse.

“Will you see Dr. Hines now?” You ask because you have nothing and too much to say all at once. “The appointment’s next Friday.”

“Sure,” he says. “It should be cleared up by then.”

When the last petal falls, you go to the supermarket and buy him a cake. You think of having them write something silly in the frosting. Something about weeding, maybe. You decide against it. After dinner, you surprise him with it. He smiles, but when he moves his arm, you notice it looks strange. Swollen around the stitches you sewed.

You reach for antiseptic ointment, but the second your fingertips press the skin, you feel something pop. The stitches unravel, the laceration reopens, and dozens of tiny black beads spill onto the table.

The suture scars on his hand and leg split with a loud tearing noise. Seeds burst from open wounds that weep neither blood nor petals, bouncing along the floor, covering white tile in black. You wrap a dishtowel around his arm like a tourniquet, but it doesn’t stem the flow.

You scramble for the phone, slipping on the seeds, knocking your chin on the counter on your way down. You grit your teeth through the pain and call 911 for the first time in your life. Charlie looks at you, through you, poppy seeds trickling from his nostrils, ears, the corners of his eyes. You can barely hear the operator over the blood rushing in your ears.

Charlie opens his mouth. He chokes. Gags. Seizes. A perfect, vermillion poppy blooms and blooms and blooms, pushing itself up through Charlie’s throat and teeth until it falls, stem and all, at your feet.

DISPERSAL

You stand at the highest point in the cemetery. Somewhere amidst the sea of headstones is Charlie and his father and brother. A bag of seeds hangs off your shoulder. Heavy. Full. Enough to fill a man.

You will scatter the seeds from this hill and let the wind and the birds take them. They will sleep in the earth until spring, then bloom blood-red in the soil of the dead, thin roots cradling the bones.