by Sophie Drukman-Feldstein

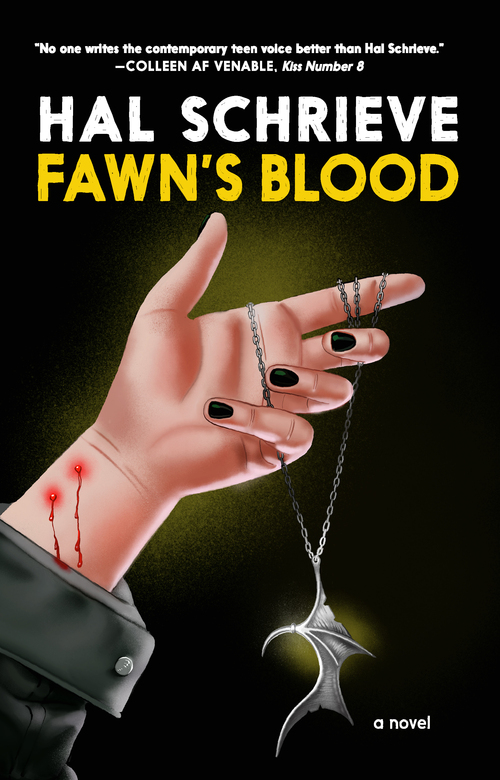

I remember first encountering Hal Schrieve’s work and thinking, “Oh, ze gets it.” Hal captures, better than almost anyone else I’ve ever read, what it’s like to be a messy, young trans person within a messy queer social scene. In hir new YA novel Fawn’s Blood, ze takes us to a vampire underworld beneath the streets of Seattle and tells a story of interdependence, survival, and the pursuit of desires deemed monstrous.

SOPHIE DRUKMAN-FELDSTEIN: First, can you tell us a bit about the book and what inspired you to write it?

HAL SCHRIEVE: Fawn’s Blood is about Fawn, a human runaway who is chasing after her best friend Silver, who faked his own death to become a vampire. She abandons her life, which she didn’t enjoy much anyway, to go hitchhike across the country and find him. And then the other main character is Rachel, the vampire daughter of a vampire slayer. Rachel and Fawn are on a course to encounter each other, because Rachel is sent into vampire communities to infiltrate and gather information for the group of slayers.

I was inspired to write it, partly, because I watched all of Buffy with my husband. I really like the monster-of-the-week format. I like the low-culture engagement with sensitive issues of the day. Sometimes they hit on something really smart. Simultaneously, there are all kinds of deviant bodies being portrayed as monstrous and constantly being killed.

I read a really good trans novel, Dead Collections, about an archivist who’s a vampire, who lives in his workplace basement because it’s very hard to find housing that doesn’t have windows. It’s set in a world where vampirism is kind of a chronic illness, where drinking from humans is absolutely taboo. None of the other vampires, supposedly, in this whole world are drinking blood. Yet somehow there are vampires. The book is really effective at showing a particular kind of frozenness people get into when they’re depressed, particularly if they’re trans and self-sabotaging away from the life they want to live. But I was also like, there needs to be more blood drinking in this.

I also read Youngblood, a lesbian prep school vampire book. It was in a world, also, where vampires never drink blood, because there’s a vampire plague that infects humans. So all vampires have relied on synthetic blood for twenty years. It’s never clear what poor vampires are doing because the fake blood is very expensive, and it’s also never clear what humans think about any of this because only very bad vampires drink from humans, and the humans are always hypnotized when that happens.

I was frustrated by that, and I was like, I would like to write about how vampirism is about desire and contact, and also has to be about community if you’re not writing about one isolated vampire in a cave. If you kill someone every time you get blood, you quickly have a problem, which is that people notice that you’re killing people. But okay, what if you need blood? You have to have a community because you have to have someone providing you the blood. And it might be beneficial to them to give you blood, because they might be getting something psychological or physical out of it.

Vampires means blood drinking. I wanted to write about the sort of desire that holds people together, even if they’re very dissimilar. I also think fear of contagion and fear of monstrosity animate a lot of the right-wing narratives about queer and trans people. So it’s always fertile ground for making very direct comparisons in terms of people hunting down our communities and attacking them and trying to kill people, and our communities not being set up to withstand such a constant onslaught, even if we have lived in the margins for a long time.

SDF: I really enjoyed the interplay between the two narrators. How did their voices develop?

HS: Rachel came to me in a flash, and I realized that I needed her in order to write this book. Initially, it was just Fawn. There was the evil middle-aged anti-vampire mom group, MAVIS (Moms Against Vampires in Seattle). But I didn’t have insight into where they were coming from, and they came off as really one-dimensional villains because they were being insane.

And then you know, you rewatch some Buffy and you’re thinking about Spike and you’re thinking, okay, a conflicted vampire. What does that look like? I think it’s interesting to have Fawn who thinks vampires are cool and wants her blood drunk, and she’s coming at it from a loneliness and a desire for connection, and then to have Rachel who is enmeshed in this very tight community that has a very rigid worldview that vampires are evil, and then she is transformed into a vampire and discovers those same desires in herself and feels horrified and disgusted and then sort of works it out. I think you needed something of both perspectives.

My other idea was to have a middle-aged guy who was a vampire. Then I was like, this is beginning to be more of a grown-up angst book than a teen angst book. I need a teen character to have this feeling.

SDF: You’re a children’s librarian who writes transgressive queer YA. What has your experience been with the current attacks on queer literature, and especially on young people accessing queer literature?

HS: I work mainly with smaller kids, and I unfortunately don’t do a lot of converting them to gay sadomasochism. I mainly just read those books about things that are relevant to their lives, as per my job description. I’m certainly trying to provide children with the curiosity and autonomy to seek out knowledge that they might not be permitted to seek out. I am part of a public librarian tradition, going back about a hundred years, which says that all children deserve an education. It originates in Victorian progressive ideals. They were very radical at the time, and it turns out they’re still kind of radical, because there are a lot of people who don’t believe that children deserve to access information. There’s people that don’t believe that adults deserve to access information.

I think public librarianship is always about trying to facilitate public education for the largest number of people possible. In recent years, more trans people have come of age who believe that even children can deal with the idea of trans people, because there are children who are trans people and children whose parents are trans people. So, there’s been more children’s literature that features trans and queer people. I think public libraries should provide that to kids. We’ve had protests of Drag Story Hour at my branch. We’ve had protests of Drag Story Hour across the system, which has diminished the number of skilled performers that want to participate, understandably, and then also diminished the amount of Drag Story Hours that the library does, because the library has decided that they need police on site every time, in case there is a protest.

I have seen the backlash in a small way in Manhattan. I am not seeing what’s going on in Indiana or Texas or Florida. I think in a lot of places where there’s a less robust brand around the library or people are not used to accessing the library as much, things might go much quieter. People might just remove books from the shelves that they think might be challenged.

Book bans went up, up, up, up, up, and then Texas and Florida had a lot of laws that targeted specifically school libraries, but also some public libraries. Public librarians have been fired in Texas for refusing to remove LGBT books from the shelves.

It’s interesting because the children’s material is very specifically designed to pass muster with all of the different authorities on children’s literature that have to say yes to something before it’s published. So a lot of them are very anodyne. A lot of them are fairly essentialist and liberal in their tone about queer identity. I often am conflicted about the queer books that exist. A few of them are quite good. There are lots of good picture books about, like, you are allowed to wear what you want. There are fewer picture books that really help a child understand what a queer person is and what they’re doing in the world, other than “two men might love each other.” There are relatively few good picture books that really dive into, like, people have a variety of relationships to gender roles, and gender roles are constructed, and you don’t have to follow them. A lot of children still live in a very rigid binary of boys’ things and girls’ things. They are marketed copaganda very aggressively. Paw Patrol is very popular.

In YA, which is what I write, there has been an outpouring of queer and trans books in the last few years. In 2010, I think the number of total trans YA books in existence was like seven, and now it’s in the hundreds.

Maia Kobabe’s memoir Gender Queer was the most-banned book in 2022. Last year it was the book with the second most calls to ban it, after All Boys Aren’t Blue, which is about being gay and Black. So, it’s like, you can’t be gay and Black. You can’t be gender queer. And Gender Queer is banned because it’s talking about linguistically defining yourself outside of the norm. It’s not about physical transition, though Maia Kobabe has pursued physical transition. It’s about the thought act of imagining yourself outside of traditional gender roles, and that clearly really upsets a lot of people.

I have not been the subject of a targeted harassment campaign, personally. My books don’t reach a large enough audience, I think, for that at this time. But other trans authors, like Andrew Joseph White or Aiden Thomas or Kacen Callender, have been thrust into the spotlight by virtue of writing about things that are deemed totally inappropriate for children to access. Trans women have mostly been kept out of YA literature. There are only three or four trans women that I can think of who have written YA at all, because I think people are very cautious about going into a field where they’re likely to be accused of being pedophiles. I think trans men are more infantilized than accused of being predators. It’s a mess out here.

SDF: Are there things that particularly appeal to you about YA, that you see as strengths or possibilities of the genre?

HS: The power to speak to a teenager and say, “You have power over your own life,” or “You potentially have power to change the world.” I think there are a lot of things that encourage powerlessness and fatalism in a lot of adult literature. The one thing that really steps outside of this is science fiction or paraliterature. There are openings and potentials in speculative fiction for adults to imagine a different future, to imagine a place that works under different rules. YA does it more bombastically. It does it more didactically. It does it louder and more on the nose, and it can use really strong images that would be considered maybe too silly in adult literature, and it can speak of emotion in really intense ways that would maybe be considered too stylistically overwrought in adult literature.

And teens have particular brains. Teens are going through a particular thing. They have enormous agency that they’re coming into all at once. Teens have the power to start revolutions or change the world. They have historically been at the forefront of things like the Arab Spring or the Russian Revolution. They have the power to flex their brains and imagine new futures in ways that people who have been living in the world as it is for longer lose.

So, I think the reason I write for teens is because you’re allowed to do more stylistically, that’s louder, campier, weirder. And hopefully you reach somebody whose brain is plastic and at the bare minimum they know that they’re not alone and that they have agency.

SDF: I liked the role that COVID played in this book. I think there’s a weird dearth of COVID art. How did that element emerge?

HS: It was partly prompted by questions on early drafts from friends. As I was initially just thinking about Fawn, I wasn’t thinking about the larger context or when it was happening. Initially, I had a whole bunch of stuff about Tumblr in there. And then I was like, Tumblr, RIP. It’s still around, but teens don’t use it quite as much. I need it to be set more contemporaneously, and then it’s like, how is COVID impacting this? And there was a blood shortage during COVID, so if there were vampires, they would be suffering. Also, the moment of mass sacrifice of disabled people that happened when both Democrats and Republicans decided, okay, time to go back to work and fuck everyone who still has immune deficiency—it makes it into the background, because the vampires have been allowed a certain amount of bagged human blood in the past. And now they can only get half of that amount, so they will all starve if they are only drinking that amount.

I think that real-world stuff overwhelms the small crisis I depict here, because the vampire population in this book is ultimately a pretty small group of people. In the real world, Medicaid is getting axed. That will affect like ten million Americans. Kids will be deprived of breakfast programs at their schools because of cuts. Every time we cut a service, there’s somebody who is not imagining the suffering it will cause, or who takes joy in that suffering. I think a lot of our politicians take joy in the suffering of specific populations of people.

I think the best COVID novel came out before COVID and is Ling Ma’s Severance. It’s about a pandemic that spreads really fast via products imported from abroad. It makes people into zombies who repeat the actions they do at work. It’s about capitalism and the relationship that the imperial core has with places that produce goods for the imperial core. I tried to have parts of that in the book, too, in terms of the sourcing of bagged blood.

SDF: It felt like you were drawing a connection between assimilation and imperial violence.

HS: Yeah. If you’re gay and join the military, then you become part of imperial violence. Or if you go to a rave in Tel Aviv, you are part of imperial violence. Some level of participation in violence is what we are already doing just by living here. But I think the more we are sold a vision of assimilation, the more we become part of that violence. And also, it can be revoked at any time. It doesn’t actually mean protection to participate in that violence.

SDF: You portray queer intergenerational dynamics with a lot of complexity. There’s also a type of intergenerational communication that you’re participating in just by writing YA. Can you talk about your relationship to mentorship and queer lineage?

HS: Yeah, all of my books are about mentorship and queer lineage. In my first book, I have an old lesbian selkie adopt a gender queer zombie who has just been orphaned. In my second book, there’s a lunatic local punk star who is trying to share in the visions of a teenager who’s seeing aliens.

In this book, I have Cain, a wacky vampire who wants to be seen as more ancient than he is, who is the subject of much gossip, who genuinely might have helped some young vampires find happiness and pleasure and community that they had not found elsewhere, but who is not going to protect them. Who will not know how to protect them, because he does not have great medium-term or long-term planning skills. He lacks specific kinds of insight.

A lot of my life has been mourning people who died before I was born because of AIDS, because of other kinds of systemic violence. Then there are people who are around, but who are insane because of what they’ve been through. And they can offer us something. They are here. They can still produce art. They can still speak to us. Many of them are very wise. Many of them are even geniuses, but they cannot sometimes do all that we would want them to do. They cannot complete the circle of care where they completely take over for all of the hurt that younger queer people have experienced at the hands of their own parents or society, because they are also suffering with their own injuries.

I think it’s worth loving each other anyway, though, also, it’s possible for us to do violence to each other. I want to talk about both of those things in all of the writing I do, because I think a lot of materials that encourage queer kids to come out, that encourage queer people to encounter each other and need each other and step into queer community, have this language of like, you will find a queer community. You will be safe in that queer community. I think sometimes that’s true, and sometimes it’s imperfectly true, and sometimes it’s not true, depending on who and what and where. Often, I find people either older or younger who have had betrayals from their own community, who have been hurt by people in their community, and who don’t believe in community. Kai Cheng Thom writes about this.

It is not a community unless we are in conversation about how to keep each other alive, and sometimes we fail at that. So, I’m trying to talk about how to stay alive and about the fact that people are gonna disappoint you, and you might wind up in a position where it’s up to you or up to people in your generation working together to fix something. But you can learn from what has happened before, and there might be people who are around who are older than you, who can help you in some ways. It’s not a vision of like, you’re going to have perfect queer Mommy and Daddy who are gonna take care of you when you step into queer community. They’re gonna be a mess, except when they’re stars and geniuses, but they might be a mess again.

SDF: What went into the decision to eroticize Richeza and Fawn’s relationship? I think the more expected choice, in a trans YA novel about moral panics, would be to have that mentorship relationship be straightforwardly wholesome.

HS: Fawn is a trans girl. I think lots of people relate to trans girls by needing something from them, even people who might be in a position to offer care or wisdom or upbringing. I wanted to write her as somebody who is vulnerable, because trans girls are vulnerable to violence. So Fawn is going through that. People are asking things of her even as she needs a lot of care. She’s a homeless runaway. She deserves care and love, but the people around her respond to her by wanting something from her, and I think that, often, that wanting in real life is erotic in nature. Or it is sort of a validation exchange. Needing to validate one’s own position as an elder, as a mentor, as somebody with power, as somebody with capital or community or housing or whatever, that can give. People want to affirm their own idea of themselves as a giving person in society.

For Richeza, I think it’s simply that she is an older kind of monster. I wanted to have an older kind of scary monster in there, in addition to some more do-good, upstanding-citizen vampires. I wanted to see what a monster-y monster would look like in this world, and she’s still not eating Fawn alive and killing her. Richeza sees in Fawn something that she needs, and she wants to preserve Fawn’s existence for the future. She wants Fawn to continue forward. I’m trying to write about a really complicated mutual need between older people and younger people in queer communities, where whether you think Richeza is an evil predator or whether you think she is someone with different cultural values from a different time, she is engaging in a kind of cross-generational contact where she’s trying more than almost anybody else to make sure Fawn stays alive. Simultaneously, she does drink Fawn’s blood.

The thing that Fawn is capable of giving to the vampires is both her literal blood and also, she is somebody outside of their circle that does not have the same weaknesses they have, and she can provide them with allyship and defense. She can be a point of contact for their continued existence. So there’s a mutuality, there’s a mutual aid happening. It’s imperfect, and there are strange power structures happening. Fawn likes her and thinks Richeza’s monstrosity is cool, and is also a little worried about how much she can give her without being hurt.

SDF: You’re both a writer and a comic artist. How do you decide what genre a story wants to be in?

HS: Comics started happening in 2020 or so, just spurting from my pen in order to process things, and I think they’re a good processing tool. I tend to be sillier and less coherent and more short-form in comics. I’ve had one really long comics project. I think I’m limited by what I’m able to draw.

I think this story would make a good comic book, but I don’t have the capacity to quite tell it in comic form. I wanted to spend a lot of time with the internality of the characters, and internal monologues can only be part of comics. You have to really use the visual part of the medium.

For my long-form project, Vivian’s Ghost, the ghost really wanted to be seen, and when I tried to write it as prose, I was spending too much time describing the ghost. So I was like, better just draw the ghost. In Fawn’s Blood, I wanted to spend time with the thoughts of the characters and to limit what the reader is seeing to what they’re seeing at any given moment.

SDF: Did the story or characters take you in any unexpected directions as you were writing?

HS: Richeza just kind of showed up. And it turns out that I really need to have some wings and bat noses and to get more monstrous to stay interested. If a vampire is just a human who sucks blood, it’s not quite all I want. I really like it when they’re turning into different shapes. One of my favorite vampire movies is Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the one that has Gary Oldman in it. Gary Oldman sucks, but that movie rocks, and there are so many different kinds of Gary Oldman vampire in it. He’s old, he’s young, he’s a wolf, he’s a bat, he’s a wet bat, he’s a wet bat wolf man, he’s flies, he’s smoke.

SDF: There’s this moment where Fawn says, “I’ve been trusting people this whole time … It’s how I got here. It’s why I’m alive.” This spoke to me, and it’s so at odds with the messaging kids usually get, that basically everyone outside of the nuclear family represents a threat. Why did you include this message of trust?

HS: I think solidarity is the only way to create a better world. I think that if you have the capacity to believe that someone very different from you can nevertheless be trusted or act in good faith, you could trust someone enough to tell them how they’re hurting you. You can trust someone enough to tell them what you need, and that might be how to stop getting hurt. That might be how to make yourself more free. I think that isolating people is how children get abused, how people get abused in general. If we’re atomized, we lose each other, we lose the capacity for organized action and social change, and we also end up suffering a lot.

SDF: Who’s your favorite classic vampire?

HS: I like Carmilla ’cause she’s cool. There’s part of it where she’s a big panther. She’s also a chronically ill teen girl who is secretly a seventeenth-century demon, right? It’s surprisingly lesbionic. I expected it to be more dry and Victorian in tone, but it was a salacious magazine serial. And then when she dies, they stab her, and her coffin fills with blood, and she screams and flies into the air and stuff, and it’s like, it’s just right. That’s just right.

I like Bela Lugosi. I like Daughters of Darkness, the 1970s movie. There’s a lesbian vampire who has an assistant who’s trapped in her thrall, and they’re in a weird hotel, and they’re gonna prey on this straight couple that comically fails to leave the hotel as they have all the time in the world to get the fuck out of there. I love that one. Dracula’s Daughter is also a great movie with some lesbian overtones. She tricks a woman into coming to her house under the pretense that she’s going to draw her, and because it’s during the Hays Code, it just zooms in on the woman’s face as she’s approaching. So the woman just looks more and more terrified as she’s being lesbianically approached by the vampire. Those are some good vampires. I had an Anne Rice phase in middle school, absolutely, as well.

SDF: Anything else you want to say?

HS: merritt k has a self-published vampire novella that just came out called Vampirocene. It’s about vampires being active agents in trying to heal climate change because they’re going to be alive longer than anyone else. I think it’s very cool. There is also a novella, The V*mpire by P H Lee, about a predatory they/them transmasc vampire preying on a closeted trans girl. It goes into some of the same concepts I was initially working with, Tumblr politics and culture, what if vampires, but Tumblr. Those are some vampire recommendations I have.

• • •

Hal Schrieve is the author of Out of Salem (2019), which was long-listed for the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. Ze also has written How To Get Over The End Of The World (2023), about teen punks and alien prophecies, and Vivian’s Ghost (2024), a comic about a ghost who won’t go away. Ze is a librarian.

Sophie Drukman-Feldstein is a writer, editor, and translator living in New York City. Their work has appeared in the Bellingham Review and Contemporary Verse 2. They read submissions for The Dodge.